Koudelka’s testimony of the Invasion

This year, the Czechs can see Invasion 68, a unique collection of photographs by Josef Koudelka (1938). The book was published by Torst and the exhibition was shown at the Old Town Hall in Prague. Invasion 1968 is Koudelka’s photographic testimony of the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Army after the Prague Spring, when there was a gradual loosening up of the stronghold of the regime. The combination of the tense historical events and the photographer’s talent created a unique photographic reportage.

Josef Koudelka never photographed anything like this before, and so he covered the situation in documentary style: he looked for situations that generalised, gestures and symbols. Perhaps that’s why Invasion 68 is a completed unified cycle with a recognisable signature. In the spirit of humanistic photojournalism, Koudelka’s reportage developed into a deeper story, into a picture essay.

His photographs of the Soviet occupation found their way through the curator Eugene Ostroff from the Smithsonian institute in Washington to the then director of Magnum, Eliott Erwitt. The photographs were published and soon almost everyone in the West was familiar with the Anonymous photographer from Prague. Thirteen iconic photographs published in numerous publications changed Josef Koudelka’s life. He, fearful of his identity being exposed, decides to emigrate. Koudelka’s subsequent nomadic life in exile and his rootlessness is best reflected in his ultimate collection Exiles (1979–1994).

While preparing Invasion 68 forty years later, Koudelka looked through all the photographs of the event again and decided to produce a new collection with 249 pictures. It is understandable that such a numerous selection has both stronger and weaker photographs. But as a whole it is a remarkable memoir of the period. The publication is a successful balance between the author’s photographic testimony and historical material. The photographs are accompanied by texts by the historians Jiri Hoppe, Jiří Suk and Jaroslav Cuhra; in the conclusion the exhibition’s curator, Irena Šorfová, explains the fate of Koudelka’s photographs. The graphic designer and co-editor of the book, Aleš Najbrt, played a significant role in the project.

The monograph is divided into themathic chapters, which loosely follow the sequence of events, while the installation of photographs at the exhibition evokes chronological film story. With 249 photographs in the book, it was necessary to create a certain visual rhythm. Aleš Najbrt places key pictures on double pages and creates a colourful mosaic of gestures, situations and places from the more descriptive ones. At the Old Town Hall exhibition, he also works with different formats. He puts together a picture story, which carries the main theme and the smaller episodes. Thanks to this arrangement, we can see the various layers of the photo collection. Admittedly, there are some motifs, which repeat themselves in the new edit of the Invasion, but from the historical point of view they have their own place there. At first impression, the banal four pictures of a soldier on a tank surrounded by people changes when we realise that he is the commander of the Soviet occupation force demanding obedience from the people of Prague who had gathered outside the Czechoslovak radio station.

Unprepared, just as the whole country was, for the situation, which started on the 21st August 1968, Josef Koudelka spent seven days taking photographs. Because he was not experience in reportage, he looked for artistic certainty in the rules he created for himself when he was working on his documentary project the Gypsies. This collection, which he started working on in 1962, has a static feel and shows an obvious collaboration between the subject and the photographer. Instead of dynamic compositions, Koudelka uses a form, which expresses the gradual disappearance of the Gypsies’ traditional nomadic lifestyle. He arranges people into stiff poses, looking questioningly straight into the camera. The scene may look like time stopped still, but the background is still vibrating with the previous drama.

The same principle is used by Koudelka while photographing the country under occupation. Unnoticed, as if he were in the theatre among actors, Josef Koudelka moves between the two hostile sides. He is not afraid to come close to people; their portraits dominate the invasion photographs. Behind the frightened and aggressive eyes can be seen other lives of problems and emotions. Instead of an old wall behind a static face we can see parallel historical events unfolding.

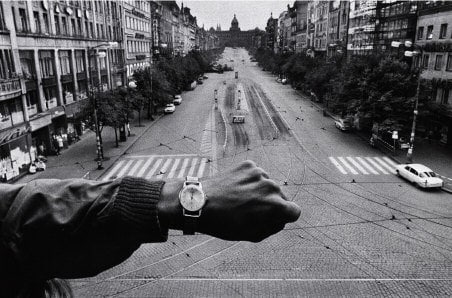

Motif, which he did not explore much in his previous work, and with which the photographer works often here, is the contrast of emptiness with a strong visual signature.We can see it in the famous pictures of the desertedWenceslas Square soon after midday with the wrist watch in the foreground, or in the photograph of a young man sitting in an empty street in front of military vehicles with a target on his back. A crop from this picture was used on the singer Karel Kryl’s legendary album Brother, Close the Gate, recorded in 1969. Together with Kryl’s cynically sad songs, the photograph looks positively icy. The emptiness in one part of the picture emphasises the emotional component of the second motif. In the atmosphere of occupied Prague the contrast is even more pressing.

Josef Koudelka didn’t want to photograph an essay about fighting and political regime. Suddenly a situation happened and he felt that it was his duty to pick a camera and press the shutter. It was obvious – his country was at stake, his nation was desperate and the photographer felt an inner connection with this event. Long time ago, similar feelings led Zdeněk Tmej to photograph Czech and Slovaks who were forced to work for the Nazis. In modern history of Czech photography these two sets of photographs have much in common. Tmej’s documentary pictures from Vratislav are a deep investigation into the tired everydayness, yet full of humour and kindness. In contrast to the one week in which Koudelaka had to take his photographs, Tmej observed the young men working in Nazi factories and prostitutes in brothels for non-Arians for the best part of two years. The parallel with Koudelka’s invasion lies in the personal presence and engagement. Both sets of photographs are exceptional, both in the Czech and global content.

Out of the numerous photographs of the Soviet army invasion, the pictures taken by Bohumil Dobrovský and Ladislav Bielik are exceptional. Dobrovsky’s photographs are full of human drama, visual certainty and symbolic meaning; they show his vision and his ability to abstract general information from concrete facts. Ladislav Bielik is the author of probably the best known Slovak photograph about the invasion in Bratislava. ‘Man exposing his chest in front of the occupying tank’ as the picture is usually called today, has become the icon of the Soviet occupation in Slovakia. The photograph, in a simple but loaded abbreviation, talks about the longing for non-violence and the need of people to join in, in the moments of crisis, to defend freedom.

Koudelka’s photographic essay is looking for all-valid laws; the most important pictures from Invasion are generalising in character. In them we can see the symbols of the time, the marks of oppression and the respect for humanity. Josef Koudelka’s photographs from August 1968 are a compact unit, which has found its dignified place with the photographic testimonies of Eugene Smith and Werner Bishof, if not higher.

#11 Performance

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face