Idols modeled by men

I.

Why is it that photographs of figures in a state of undress so often strike us as kitsch, that is, as “a sleek image untouched by the divine inspiration of art”?[ref]Váša, P., Trávníček, F., Slovník jazyka českého. Prague: Fr. Borový 1941: 789.[/ref] This was the original issue I was going to pursue. After all, the inability to work with the nude has damaged the reputations even of artists regarded as undisputed masters in other genres. In working on this essay, however, I realized the futility of looking for answers to the genre of the nude solely within the domain of art.

II.

One of the impulses for the contemplation of femininity as constructed by men was provided by an exhibition of silver daguerreotypes in Vienna – Inkunabeln einer neuen Zeit. The juxtaposition of a young nude girl with what was almost her mirror image, a statue by Hans Gasser, demonstrated that gypsum can never completely portray the feelings of shame which possess the live model the instant she realizes that crowds of people will be queuing up in front of the showcase containing her effigy: though we may not be personally acquainted with her, we perceive her as a concrete human being. The author of the somewhat shaky 1849 nude, Félix Jacques Antoine Moulin, did not exclusively hire hardened professional sitters. He also consigned his wife and daughter to copper and silver, the latter from the age of two until the moment captured in the picture that I saw on my visit to the Albertina gallery in the fall of 2006. His portrayal of naked femininity scandalized the French Court of Justice… and I went through the entire catalogue twice before finally being able to believe that Moulin’s statement on the human condition was indeed not included in it…

Photography is a technique that makes most viewers forget how the image was made, particularly when the artist is aiming for naturalism. In paintings, engravings and drawings, we see not only he motif, but also the artist’s rendition of it. His energy is preserved – indeed, manifested – by the traces of the creative process. In contrast, the technical image easily conceals these traces. While dilettantish paintings or drawings only seldom manage to charm us, technical images have the power of astonishing us even if they have nothing to do with the history of art.

Toxicology professor Jiří Patočka: “The biochemical processes which take place in the brain when we look at the photograph of a beloved person strongly resemble cerebral activity under the influence of cocaine. It would appear that oxytocin works together with natural opiates occurring in the body, endorphins. Oxytocin provokes the drive towards forming social relations, while opiates administer the sensation of warmth that we experience in the proximity of the persons we love. All the substances cited here are in fact natural drugs.”[ref] Patočka, J., Jak funguje chemie v těle a drogy v přírodě. MF Dnes 12. 5. 2007; 18/110: C10. [/ref] Hence, as handed down by tradition, the infernal origins of photography and film.

III.

Theoretical disputes as to the nature of art preceded the invention of photography. Euro-American nudes emerged in an environment strongly marked by Christianity: even as late as the 21st century, some atheists still feel an intense need to commit blasphemy. In and of itself, however, exposing taboos does not offer the desired legitimacy, and when presented as art it becomes (often less-than-sleek) kitsch. I have no illusions about the intentions of artists from other cultures (Nobuyoshi Araki, Kishin Shinoyama and Noritoshi Hirakawa are regarded as kitsch-mongers by many Japanese), but the precise mechanism of their sins against their culture is alien to me. On the other hand, we are all programmed more by our biological nature than by the diversity of our civilizations. This, too, is one reason why photographers who aspire to the status of artists are motivated to recast the model, a fact of life, into an inspired image. The technology of the medium of photography, nonetheless, would seem little suited to the purpose of idealization. Even hand-coloring, striking today in its naivety, had once been a device which hoped to convey the world of natural color; by stylizing the motif to evoke an Edenic idyll, the author hoped not only to gain an alibi to use in front of the moral police, but also found a means for overcoming the prejudice of the more hypocritical viewers: after all, there was no shame before tasting the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. By adding external attributes, artists simulated scenes that the audience were accustomed to from the picture galleries.

Photographers had inherited the nine Muses of ancient Greece. Attributes were often applied so loosely that many muses cannot be identified in such photographic rendering – an apt foreshadowing of the future tabloidization of the media.

Although celebrations of motherhood and the elevation of its physical signifiers can be found in various cultures since time immemorial (the history of visuality would be barren without their changing forms), the orthodox representatives of religious doctrines and various later ideologies failed to embrace their directness. For them, technical images revealed corporeality in too naturalistic a manner. The body was thus covered in maillots (as tight as possible, so that corporeality would not be lost altogether) or retouched. Often, even this was not enough. In the late 1920s United States customs officers in Seattle seized unretouched nudes by Drtikol and threatened to tear them up by the authority of their office (in the end, they did not do so).[ref]Birgus, V., Braný, A., František Drtikol. Prague: Odeon 1988: 28[/ref]

Such unyielding prohibitions were circumvented by innocuous photographs passed off as “keepsakes.” The widespread popularity of portrait photography is usually explained by its technical ease: hand-painted miniatures were replaced by the more automated photographic process, which also gradually made portraits cheaper – so much in fact that these days we immortalize our image ourselves… The convenience of the medium is indeed an important factor. The adventure, however, lies in overcoming contemporary stereotypical thinking.

One could start with the legend of Veronica’s veil. Veronica is said to have taken the imprint of Christ’s face on the slopes of Golgotha not once, but thrice: the cloth of the “veil” was folded. This brings us to the moment when a picture’s addressee is no longer concerned with uniqueness, but holds fast to authenticity…

It was not “a towel such as you might throw into a boxing ring, but a sudarium in which Christ’s perspiration (i.e., Latin sudor), mixed with his blood, was said to have imprinted the features of his face,” critic Michal Janata wrote to me as soon as he read my essay on the ontological contexts of the Veil of Veronica.[ref]Moucha, J., Zážitek arény. Bratislava, Fotofo 2004.[/ref]

In any case, the Trinitarian nature of Veronica’s relic violates the Old Testament’s Ten Commandments in a most remarkable point: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”[ref]Exodus (20, 4)[/ref]

IV.

Since 1903 saw, thanks to the initiative of Františka Plamínková, the founding of the Czech Women’s Club (Ženský klub český), whose aim was the cultural and political development of Czech society, let us look at a portrait of a lady from this time – an exemplar from the studio of the unusually productive photographer František Krátký. Krátký was clearly interested in adoring his model – one of the time-honored reasons for representation. In my thirty years of scouring through second-hand bookshops offering photographs from scattered estates, I have not come upon another symbolization of an aureole in a rectangular shape, while there are innumerable ovals inscribed in photographs. The model bears a remarkable likeness to Bohumila Bloudíková, who apprenticed with František Krátký in Kolín. In the spring of 1906, she opened a studio of her own in the same town. Her successful competition with her colleagues in Kolín is all the more impressive considering that the town is much smaller than nearby Prague.

In the 1920s, the women’s movement gathered momentum. During the protracted war, European men had evinced a certain degree of expendability. While they waged war, the women stayed at home and took care of their offspring – the longer the absence, the more independent the women became. They survived the horrific exploitation of the hinterlands to feed the conscripted army on the front. Those men who returned, returned to a world that had changed.

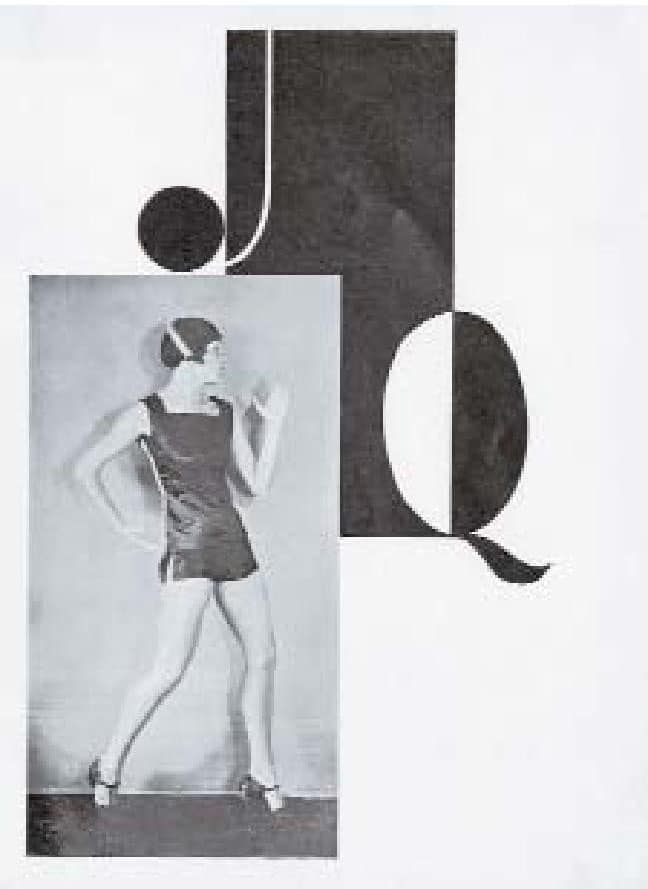

European and American women of the 1920s cast off prudish dress codes. They shortened their skirts by a third and went swimming in bathing suits that no longer threatened to drag them to the bottom with their heavy lacework. They were also seen more frequently in sports suits. A scene featuring dancer Milča Majerová beautifully captures the modern staging of dance and creativity whose focus was woman – here staged by Karel Teige.

The clandestine eroticism of art nouveau was replaced by realist stylization… What persists, though, is the extremism of male fantasies about the dual role of the mother-saint – that hard-working matron of home and hearth – and the unchaste object of sexual abandon.

In order to expand the image of femininity, it had to be interpreted and conceived socially and critically. Genre pictures survive to this day, but formal aesthetization, confronted with the non-illusory depiction of the social classes, has diminished in significance. This occurred particularly during the world wars and in the economic crisis in the 1930s.

V.

In those European cultures that were afflicted by the doctrine of socialist realism, until relatively recently theory sought to dictate both subject matter and style. Inevitably there occurred a clash of authority and authenticity (a phenomenon not limited to the past in Communist totalitarian regimes).

In the genre of the nude these contradictions manifested themselves with more than the usual degree of absurdity. At first, the nude was not tolerated at all. The genre was remote from the issue theoreticians of Socialist Realism had at heart: “an art of the Communist Party, consciously engaged in the struggle for the victory of communism.”[ref]Šabouk, S. (ed.), Encyklopedie světového malířství. Prague: Academia 1975: 329.[/ref] In the advanced Central European countries, with their rich avant-garde tradition, a total sterilization of genres was not possible. Their suppression, however, was achieved by the expropriation and monopolization of the printing industry, the censorship of museums and galleries, and the monitoring of creative effort through artists’ unions. The bodies represented in photography were those of Stakhanovites (Soviet-style “shock workers”) and athletes.

In the Czech lands, just about everything was kept in a corset until the very end of Communist rule. In their magazines, the chief editors of 1970s and 1980s periodicals – members of the ruling party who often had been appointed to their jobs during the purges following the crushing of the Prague Spring – did their best to hide the fact that a new era had begun. In the meantime, the generation of flower children shunned the barber, imported loose ethnic cotton garments from India, and psychedelia emerged from the subconscious and hit the shelves of European and American clothing stores. Afro-hairstyles were all the rage, and mini-skirts were arrayed next to trouser suits made of 100% polyester. Bra-less girls walked the streets of Bohemia as well, but when it came to fashion photography, they had to pretend they wouldn’t be seen dead without the vestiges of the corset.

That said, one cannot but think of Jan Saudek, one of the rebels of those days. With a characteristic sense of paradox he once said (in reference to his 1974 Marie No. 142): “No girl is going to hold her blouse up in her teeth in order to reveal her breasts. I posed her like that, and it worked.”[ref]Fryšarová, R., Jan Saudek. Foto Video 1999; 6: 8.[/ref]

VI.

Even the less observant reader has by now certainly noticed that I have omitted contemplating on beauty as the compromise of a herd-minded jury in a beauty contest. All these homecoming queens are too alike (perhaps we could say “poster-like”), for they are a variation on vulgar academism. Attempts at pleasing as large a crowd of consumers as possible by offering them an idol in a doomed massage of the public mind are more than embarrassing.

This is all the more reason for women artists themselves to set to work at making their own portrait – a more than usually heroic chapter of the democratization of art. Initially, this process mostly showed that the male ideal of usefulness had taken root even among women. Bu they had little choice if they wanted to assert themselves in a male-dominated field… As an example of a turning point we may cite an artist who regards the contemporary social order with a very critical eye – documentary photographer Dana Kyndrová. Her book Žena mezi vdechnutím a vydechnutím (Woman Between Inhaling and Exhaling, 2002) captures the process of identification with the female role since early childhood, when children imagine and act out adulthood in their games. The book subsequently reveals, in many variations, the reality of women’s productive years. For the most part, it is exhausting drudgery – no matter whether women have asserted themselves in white collar or blue collar jobs (such as the poultry executioner seen among the hooks in a meat plant). Kyndrová pays praiseworthy attention to sexuality: the women in her pictures are seen as objects of various situations (a beauty contest, an erotic festival, a strip-tease show) or have themselves done up in hairdressing parlors to win male attention, give birth, and start the whole process over again. Kyndrová is also clearly fascinated with what happens when women decide to imitate men.

VII.

It is here that I see an answer to the question put at the outset. Men depict women simply in the way they want to see them. Not only through the prism of the ideal; even the naturalism of pornography is a far cry from reality. When faced with the richness of real-life womanhood they are at a loss. For this reason their visions become obsolete with the change in popular taste. This is true of most works, even those by more timeless artists. With artists such as František Drtikol, the illusion of timelessness is created by the fact that only that part of their legacy is regularly displayed which is less susceptible to the ravages of time. Even artists who specialize in fields other than the nude fail where they lack assurance (as is attested by the titles of the artifacts alone). A true perspective, however, is not guaranteed so much by experience as by judgment: If an artist had visual talent or inspired thinking, he or she would not publish artistic attempts of dubious quality.

An ongoing debate in the photography of the last century was the one between pretense at art and pretense at truth. If documentary photography is recognized at least by some as art today, this signalizes a partial shift in sensibility. This shift was assisted and perhaps even achieved by our experience with documentary films, which is significantly different from our impressions from television news coverage or feature films and their idols.

Documentarism effected the climax of the struggle with photographic and cinematic denial of existing reality through its beautification. The documentarists applied the most unexpected (and thus surprising) revolution against the classical theory of art. As a result, Mukařovský’s structuralist definition of the aesthetic function has ceased to be the defining line of what is art and what is not.

Most works printed in differently conceived volumes on the history of photography continue to be produced by men – a position which they hold from the oldest pictures up to contemporary works. The visual accompaniment to this essay copies this trend as well, though the examples from the history of Czech culture are more generally applicable. If a sign does not match the object whose shadow it appears to be, it can also tell us something about the author. At times it is no longer clear which of the photographs were posed and which were staged by life itself. Tibor Honty’s snapshot He Fell in the Last Seconds of War. Funeral of Colonel Georgy Sakharov in front of the Rudolfinum, Prague, May 10, 1945 strikes us as fiction. You couldn’t stage more pathos even with a Hollywood crew at your beck and call.[ref]Moucha J., Déja vu. Fotograf 2005; 4/5: 106.[/ref] The anomaly of Socialist Realism finds a parallel with the national realism of Hitler’s Germany. Sculptor Jan Koblasa, who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, defined the rendezvous of these two contradicting tendencies as the “territory of kitsch”.[ref]Koblasa, J., Záznamy z let padesátých a šedesátých. Brno: Vetus via 2002: 67.[/ref]

Even though the number of women photographers has grown steadily since the Second World War, it still took them a long time to come to terms with the persistent prejudices of the more robust sex regarding the so-called frailer half of humanity. Nonetheless the images spread by male photographers about the gentle creators of this world are becoming increasingly relativized. The male hegemony in the field of photography is being broken down by digital technology, which does not pose the same kind of barriers to women as the wet process. But this is another story…

#10 Eroticon

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face