Oleg Kulik

oleg kulik, or the flying dog man

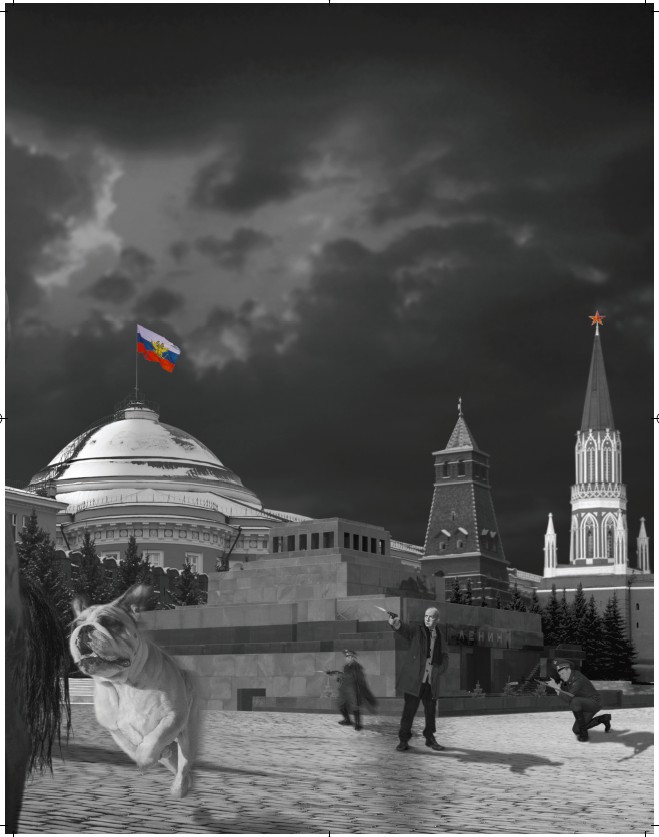

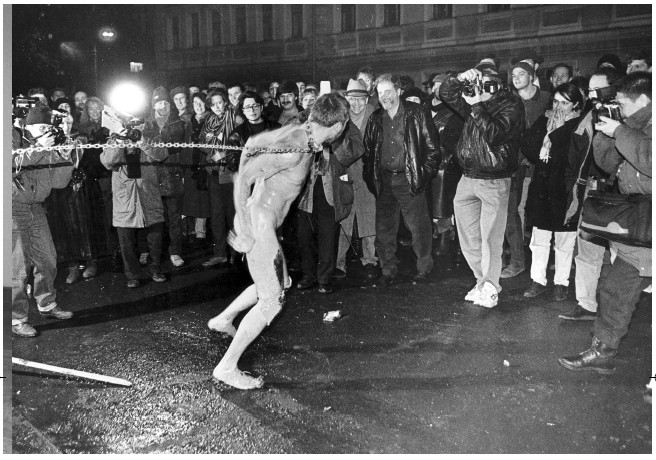

On the other hand, Kulik reacts to a completely different situation both in politics and art than the aforementioned artists had addressed. There are further differences, but there remains a basic artistic mood or temperament that is very similar. Kulik’s 1996 action I Bite America and America Bites Me in the Deitch Projects gallery in New York (Kulik was locked up like a dog in a booth inside the gallery and would communicate with the viewers through a slit by barking and growling – the more courageous viewers could enter his pen – at their own risk, as there was an element of danger involved) – paraphrases Beuys s famous coyote performance dedicated to America. There is a level of polemic with Beuys, especially so far as concerns the relationship to America, but at the same time it is – perhaps unconsciously, claiming allegiance to Beuys artistic tendency. Kulik’s provocation of society and art may in fact stem from the same roots as those of Beuys, but what seems clear is that the cup of his patience is not merely overflowing, but bursting forth. The single-mindedness and rage we sense in Kulik’s performances of the 1990s may be closer to David Lynch’s Wild At Heart than to Beuys’ mystical Christian philosophy. It is as though there was no longer room for Christianity and mysticism (familiar to Kulik via his preoccupation with Tolstoy), as if the feelings of being wounded, being excommunicated, the unbearable nature of postmodern media culture programs reached such intensity that one can no longer say anything, one can just bare one s teeth and bark. Kulik’s performances are the result of a far greater intensity of disgust with the contemporary world and art than was ever reached by the “Kulik predecessors”. The level of empathy with those who do not belong in the contemporary world also differs. I Bite America and America Bites Me and all the Dogman performances have this symbolic dimension too. The hungry dog, kicked out, is apart from other things also a metaphor for the artist who has no place in the contemporary Western art establishment (the embargo of the West on Russian and East European art in general). The performances have other levels of meaning, though. Firstly, there is the philosophical level, his refusal of the anthropocentric conception of the world. One must also not forget that the aim of Kulik’s performances is a personal experience – to feel at first hand what it feels like to be a banished, stray dog. In 1964, Joseph Beuys founded the political party of animals, and was absolutely serious about it. But Kulik went even further and wanted personally to experience the feelings of a stray dog. When he ran naked and on all fours through the streets of Zurich and Berlin, getting arrested, what he came out with was not an opinion on this issue, but a lasting psychosomatic experience. In a similar way, Chris Burden experienced what it feels like to be shot (his 1971 performance Shot in Santa Ana), unlike viewers consuming TV shows full of shooting and murders. And similarly, the now virtually unknown performer S.B., who exchanged her life for a week with a prostitute in a cheap brothel in the Amsterdam port area. Kulik also needed to personally experience pain and suffering, in this case the suffering of a stray dog. Moreover, Kulik’s empathy with the world of animals has individual motivation, and his sympathy with animals goes back to a childhood trauma. All possible connotations are also present in Kulik’s project Deep Into Russia, including the interpretation of the famous saying “Russia cannot be understood by reason”. In 1993 Kulik returned to live in the countryside, in close relationship with nature and animals. The output of this performance is a collection of photographs and a film, featuring, among other things, hints of copulation with animals. Kulik does not understand reality as an ideological or political construct, but rather as a space in which the lives of animals and people are linked biologically and fatally. The performance has another level referring to the nature of the artist’s link to reality.

The perception and participation of reality, however, is but one aspect of an artist’s work – another aspect is the way of representing reality. In 1995 Kulik jumped out of the window of a St. Petersburg flat and floated in mid air, suspended on ropes. He called this performance In Fact, Kulik is a Bird. The title is a pun: in Russian, “kulik” means a woodcock. The output here is a video. These two circumstances are significant – Kulik here refrains from the raw and immediate gesticulation and chooses more of a “subtle artistic work”. He does not have in mind a return to a basic, primordial awareness of a unity with nature, but creating an artistic image – in this case an image-concept referring to certain archetypal forms of consciousness. Kulik here is an artist who does not act outside of culture, who is not involved in anti-art (to use Beuys’ term), but here fully enters the labyrinth of human culture. He paraphrases the myth of Icarus, though he acts out the role of Dedalus rather than Icarus. Kulik’s directness of artistic metaphor in the context of post-conceptual intellectual sophistication works is not read by the viewer as naive, but as forceful. In Fact, Kulik is a Bird again, in a unique, “kulik” way demonstrates the archetype of human determination, and the desire to transcend that determination, of human mortality and the desire to become immortal, of the human condition as a non-flying biped, and the desire to be an angel. In this performance naturally the experience of flying was important, but this time Oleg Kulik concentrated also on the quality of artistic metaphor and on the question of the video recording itself, which is no longer simply a documenting of the performance, but an artifact.

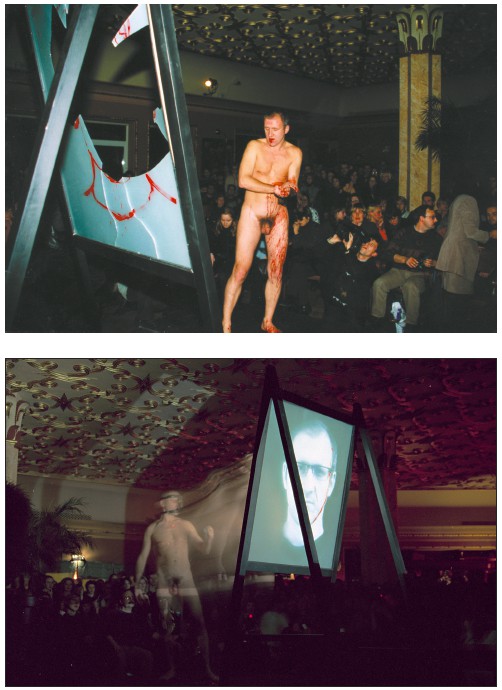

The mythical dimension is also present in Two Kuliks, performed several times, including in 2000 in Prague. The naked Kulik converses with his image, video-projected on a glass panel. The myth of Narcissus, expressing the basic nature of the act of art is however considearably modified in Kulik’s rendition. The conversation is far from pleasant, Kulik portrays his double cruelly, addresses him roughly and unceremoniously, with hatred rather than love. This painful dialogue eventually leads to aggression. With some kind of a beak fixed to his face Kulik breaks the glass pane which shatters into pieces, and the result is as it were an antithesis to Dorian Gray – the author survives and the picture is destroyed.

In the 1990s Kulik was rethinking the question of representation in art, necessarily coming up against the problem of symbol in art. With his vintage directness he chooses easily decipherable symbols, easily legible, familiar to the viewer from cultural mass production. This is evident in Armadillo for Your Show performed in 1996, which uses all the “symbolic crutches” of mass culture. Dressed in a suit made of bits of mirrors he rotates and glitters to the rhythm of disco music. The decorativeness, theatricality, posing, exhibitionism, discotheque glam, the cheap effect – all of it becomes for him the language of his work, he includes all into his art as elements appropriately presenting contemporary life.

Circa 2000 Kulik also starts working with digital photography, using it from the start as a medium of advertisement. He works with digital photography precisely because it is the ideal medium for advertisement. Kulik swiftly apprehends the aesthetic of billboards, the aesthetic of music videos – in short, the mass media strategy is to him an inexhaustible source of information. There is a saying in Czech – “You get the largest share of the thing you most deny” – which is a very apt descriptor for Kulik’s work of the recent years. And yet we can understand Kulik, it reminds one a little of Burden s performances in which he would pay for TV time and have people say names like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Picasso, together with the name Chris Burden.

In the meanwhile, however, the mass media strategies became more subtle and perfect. Moreover, Kulik’s attitude to the language of advertisement is not ironic so much as it is utilitarian. Mass media turn to address the mass viewer, not the sophisticated viewer of some art milieu. This was the kind of viewer Chris Burden may have had, as did Kabakov before his departure from Russia – the circle might have been small, but faithful and initiated. Today no such viewer exists. The artist turns towards an unknown audience, not knowing who will fish the bottle with the message from the ocean of information. Kulik turns to the mass viewer and thus he needs to master the language of the mass media.

In Museum, a project realized at the XL Gallery in Moscow in 2002, Kulik evokes the atmosphere of a natural science museum of the nineteenth century, where instead of stuffed lions and reconstructed whale skeletons we find wax figures of the heroes of our day – a famous Russian female tennis player, an astronaut, Madonna – dummies of real people who nevertheless arouse suspicion that their models are even more zombie-like than the wax copies. In Museum Kulik seems to be agreeing with Rousseau’s views on culture (familiar to him from his Tolstoy studies) as an aggressive force destroying human nature. The feminine figurines are especially eloquent on the point of morbidity, the aggressiveness of stereotypes and the ikons of contemporary culture.

From the point of view of photography, perhaps the most interesting projects by Kulik are Windows, New Paradise or Museum of Nature, realized in 2001: The resulting artifact here is a c-pring. In Windows, human figures are merged into digitally manipulated photographs of nature and animals. These humans are hazy, indistinct, as if they were behind glass, reminiscent of ghosts. They are even less real than the landscape or certain animals(a lion, a gorilla, a giraffe…), that invariably dominate the center of each photograph. In New Paradise, human erotic games are composed into panoramas of landscape, animal copulation or fighting and hunting scenes – as if people could return to the embrace of nature thanks to the sex act, but the unreality, the virtuality of these human figures is very striking here. The very beauty of large format color photography plays a role here, as it looks like something out of a travel agent’s catalogue, or a romantic encyclopaedia of animals. The unbearable perfection and idyll speak for themselves. New Paradise is like a kind of kitsch image of people, animals and nature, in an artificial paradise.

The most significant element in Kulik’s last projects is the artist’s outlook on human culture, which seems like an artificial, virtual, entertaining projection of the world, without any reality whatsoever, without any truth or grounding. Artists like Chris Burden, Joseph Beuys or Terry Fox, with whom we compared the early work of Oleg Kulik, although very critical, never went beyond the bounds of a humane understanding of human culture. Oleg Kulik’s perspective is post-humanist, as if we were being observed by an eagle or a woodcock, and it seems, that for a flying anthropo-zoomorphous creature the world of human culture contains not a grain of soundness.

#3 Transforming of Symbols

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face