Hazel Larsen Archer

Seeing Beneath the Surface of Things

The photographer Hazel Larsen (later Larsen Archer) came to Black Mountain College as a student for the Summer Institute in 1944, where she took classes with Josef Albers. She returned in 1945 to study full-time as a graduate student and counted as her instructors over the next several years Buckminster Fuller, Lyonel Feininger, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Walter Gropius, and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall.There was no photography department at that time at Black Mountain College, or even a full-time teacher of photography, both of which would be finally established in 1949 with the appointment of Larsen herself as faculty. If any one thing can be summarized about what Larsen learned from her graduate work, it is that she learned to see. This aspect of seeing is the critical one she would employ not only as a photographer, but as a teacher.1

Black Mountain College is a mythical place. With its evocation of both the European and American avant-garde, it projects the enigmatic utopian energy of Bruno Taut’s 1917 paper project “Alpine Architecture,” a city built of crystal by its inhabitants. Nestled in the hills of North Carolina in the United States, on the shore of aptly named Lake Eden, Black Mountain College (BMC) was a progressive liberal arts college founded in 1933 during the Great Depression by John Andrew Rice and based in part on the pedagogy of John Dewey.

In her 1987 history The Arts at Black Mountain College, Mary Emma Harris writes, “Black Mountain was in many respects the spiritual heir to the Bauhaus. They shared a common experimental and anti-academic spirit, a belief in the social responsibility of education and the arts, and an organization that involved both faculty and students in the decision-making process.”2 This sort of communal effort and transparency was at the heart of Paul Sheerbart’s 1914-fantasy essay,“Glasarchitektur,” which inspired Taut’s project, and was the aspect that would lead to a better society. This belief was also at the core of the Bauhaus under its first director, Johannes Itten. To no small degree, the environment at BMC was shaped by Rice’s key hiring of Josef and Anni Albers, who came to teach at BMC in 1933, having left Germany due to the rise of the National Socialists and the shuttering of the Bauhaus. With Albers, BMC became a social condenser of the avantgarde, and the roster of its faculty and students included: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Clement Greenberg, Franz Kline, Jacob Lawrence, Ben Shahn, Aaron Siskind, Ruth Asawa, John Chamberlain, Ray Johnson, Kenneth Noland, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, and Dorothea Rockburne.

Surveying the landscape of significant twentieth century figures in the arts, it seems everyone was somehow connected with BMC. Like Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in New York City, BMC was a meeting point for artists and a conduit for the absorption and dissemination of European avant-garde artwork and ideas in the United States.

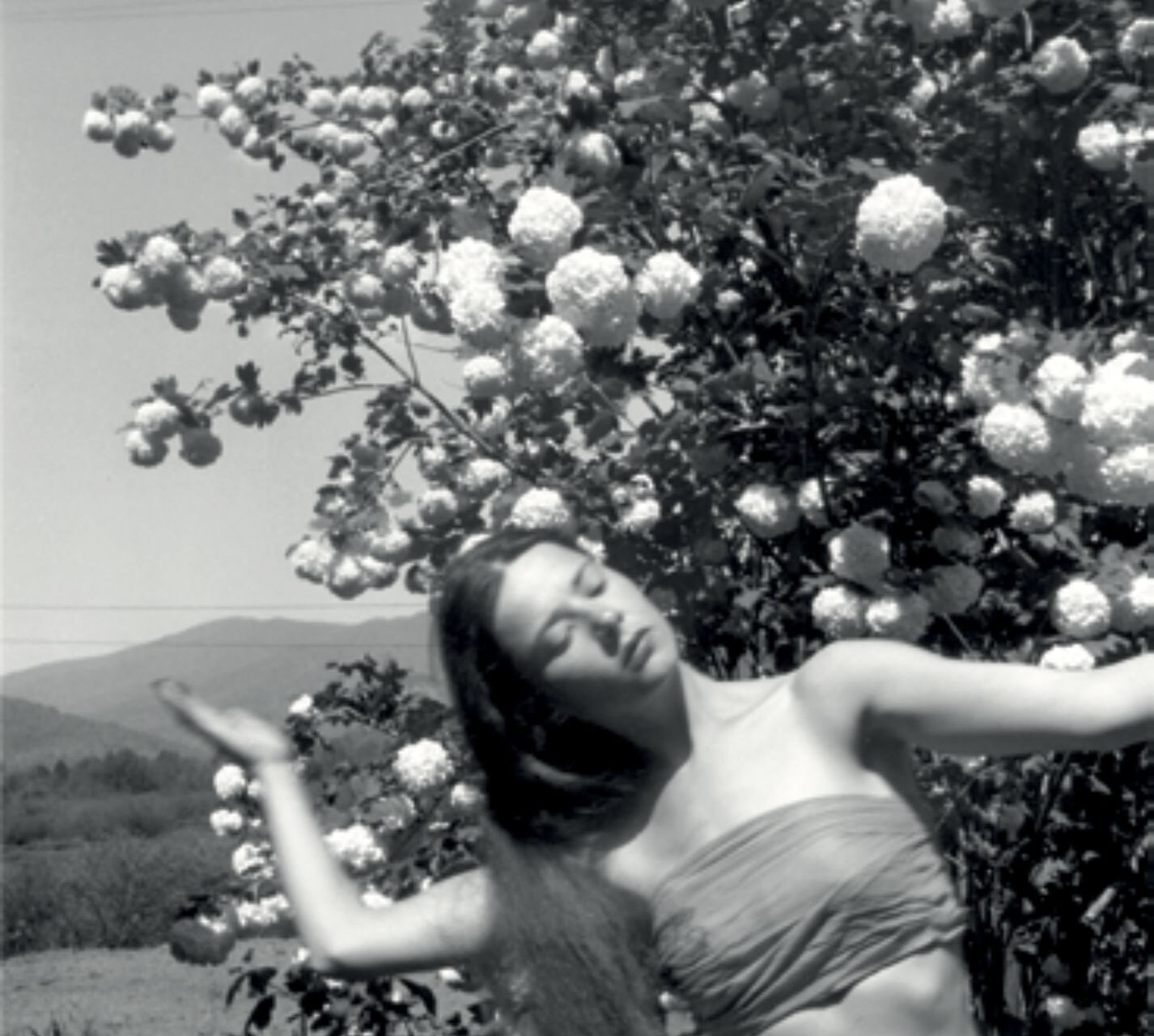

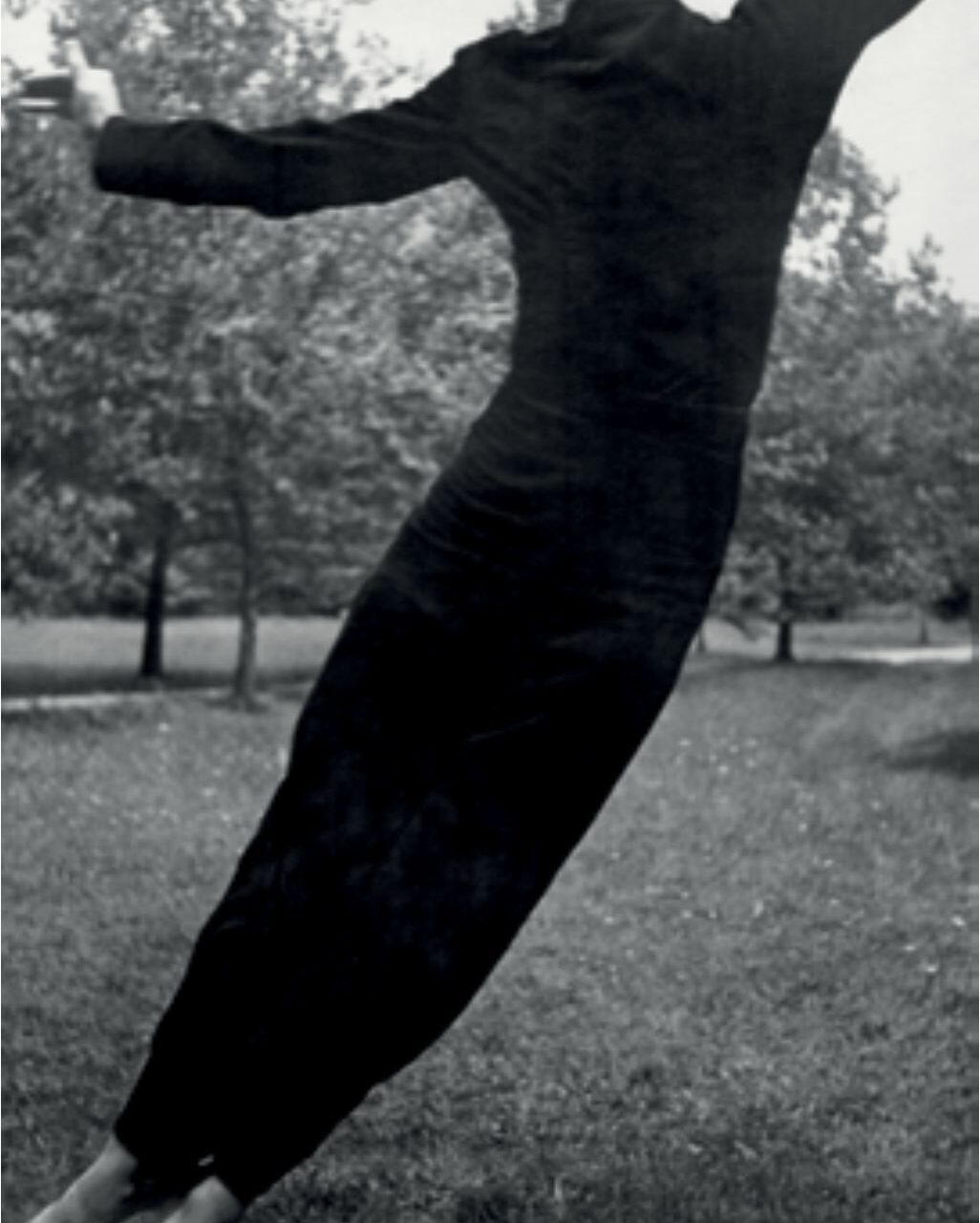

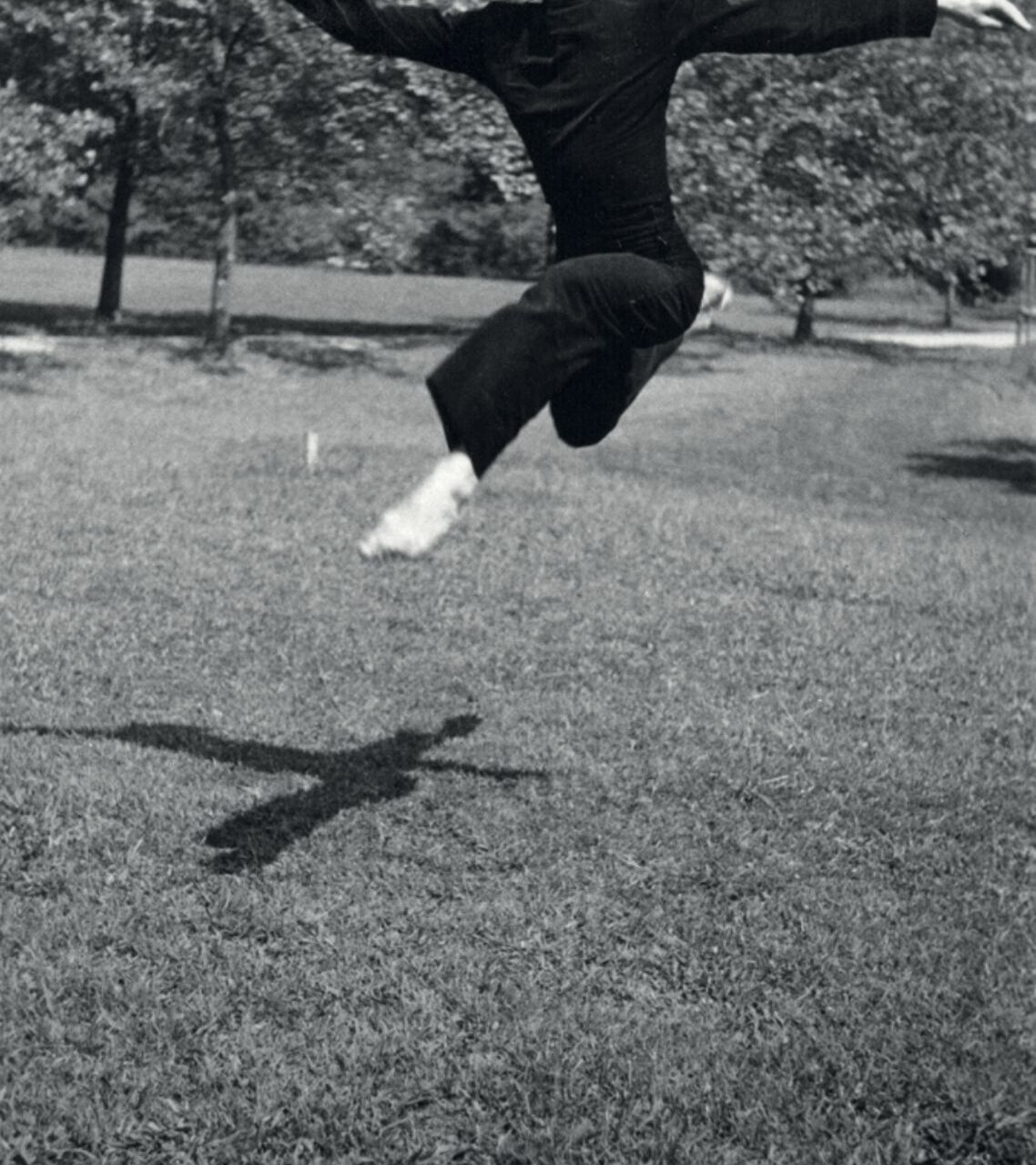

As a photographer, Larsen showed others how to see. As a teacher, she taught others to see. In a 1955 letter of support for a Guggenheim Fellowship, Fuller wrote, “She saw what we who hurry never have the time to see. She saw life processes…she saw the tree breathing…and she let us see with her what we had never been privileged to see before.”3 Fuller identifies the specific subject of some of Larsen’s photographs—trees and nature—as can be seen in her photographs of tree branches against the sky, such as Untitled, or in the study of some sort of internal dynamic of nature that can be seen in Untitled (Photogram). Fuller also describes his portrait by Larsen, Buckminster Fuller,“…I know that she saw me thinking and what I was thinking about that the pictures made people understand what I had been unable myself to tell them about my structures and their mathematical significance.”4 In his letter, Fuller also likely draws attention to what is arguably Larsen’s most famous series of photos, ones that she took of Merce Cunningham dancing that abstracted movement and emphasized negative space, such as Merce Cunningham. Fuller wrote, “And those who danced knew that she had seen in their dance and made visible to others that which their dance had been unable to communicate directly.”5 According to David Vaughan, who interviewed Andrew Oates, a student of Larsen’s at BMC, Larsen would frame or crop in the camera, never in the darkroom; she often wrote “do not trim or crop this photograph” on the backs of her prints.6 This specificity in regard to the image is particularly significant, as Larsen generally neglected to title or date her photographs. This idea of the photographer seeing beneath the surface of things and of the photograph allowing others to see it, or for the photograph itself to communicate it, is at the heart of Larsen’s practice and the means of understanding her work. With their interplay of highly contrasted shadow and light, tones of black and white, rigorous geometry and organic patterns, photographs such as Quiet House Doors, a student-built meditative space or retreat, reveal the almost spiritual essence of seeing that is beneath both the practice of photography and the experience of living at BMC.

1See Erika Zarow, “Capturing Light,” in Hazel Larsen Archer: Black Mountain College Photographer, exh. cat. (Asheville, NC: Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, 2006), 19.

2Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1987), 245.

3Buckminster Fuller, “John Simon GuggenheimMemorial Foundation Confidential Report on Candidate for Fellowship,” (1955), in Hazel Larsen Archer, 90.

4Ibid.

5Ibid. Fuller could have also been referring to the photographs Larsen took of Robert Rauschenberg dancing with Elizabeth Schmitt Jennerjahn, orthose of Jennerjahn individually.

6David Vaughan,“Motion Studies: Hazel Larsen Archer at Black Mountain College, Apeture, no. 179

HAZEL LARSEN ARCHER (1921-2001) was an American photographer who both studied and taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina between the years 1944 and 1953. She was appointed the school’s first full-time professor of photography in 1949 and stayed until 1953 before her appointment as Director of Adult Education at the Tucson Arts Center, an organization that would become the Tucson Museum of Art. While her work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art and the Photo League in New York City, Larsen stopped exhibiting in 1957 to focus on her work as an educator, disseminating widely the principles she learned and taught at Black Mountain.

THOMAS BEACHDEL, PhD is a professor of art and architectural history and theory in New York City. His primary research interests focus on landscape aesthetics/ideologies between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries and the history of photography. He is presently working on a book on the visual culture of the sublime in the eighteenth century and one on the phenomenology of darkness.

#36 new utopias

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face