Baňka’s Reflections (and the need for a conflict of interests)

At the start of this review of Pavel Baňka’s monograph, it is a good idea to avoid the suspicion of any conflict of interest ensuing from the photographer’s post as the editor-in-chief of this periodical. This role has long allowed him to influence not only the focus and content of the magazine but also the image of art photography at the Czech and international levels, where domestically it is visibly comparable only with the activities of the historian, theoretician, curator, and educator Vladimír Birgus. However, the constraints associated with the presentation of his own works act as the counterpart of his privileges. As a result, the image of Czech photography, as modelled by the magazine and its younger siblings – the Fotograf Gallery and the Fotograf Festival – is particularly skewed. Pavel Baňka is ubiquitous within it but, at the same time, invisible as an active artist. This paradoxical situation leads the author of this text to believe that a violation of the rules is in the interest of at least partially correcting this deformation. The book entitled Reflection1, the first of the previously announced three volumes of Baňka’s artistic recapitulation, appears to be a good opportunity to at least briefly recall who Baňka was, who he is – and how he wants to be perceived as a photographer.

Prior to last year’s publication of Reflection, Pavel Baňka (born in 1941) organized three eponymous exhibitions in Prague, Ústí nad Labem, and Amsterdam. At them, he presented some things from the contents of the book but never copied it. The exhibitions cannot, therefore, be viewed as mere marketing for the book, but rather as one of the products the photographer has long signalled, reinforcing the need for retrospective reflection. It is as if Baňka is suggesting that looking back never leads to finding one’s own identity – some type of being in a close-fitting protective suit from the photographs – but again and again only to a pile of negatives, enlargements, and digital data that can be handled anew and differently. Apparently he has worked “too long” as an educator and the editor of others’ works to not be substantially aware of the importance a change in accent plays in relation to the appearance of the whole. For instance, in Ústí nad Labem, he invited other artists to create a counterbalance for his photos, which drew attention particularly to the issues of personal and artistic ties, the typology of commentaries, supplements, links, etc. The selection of photographs in the printed publication can therefore be considered a permanent fixation of one perspective of interpretation, while the exhibitions were its shorter-term parallels.

In any case, taken together, the book and the trio of exhibitions may be seen as an expression of a different side of Baňka’s approach to creative works, which historian Pavel Vančát has summarized in the monograph as the impossibility of tracking down “a fixed and unified line”. At this point it should be mentioned that in no way does this infer the result is a chaotic mishmash. What we have is more of a work that, over time, has undergone multiple twists and turnarounds but, at the same time, has often been born as the concurrent arrangement of a greater number of collections requiring different (sometimes even far removed) approaches. It is specifically in this way that Vančát’s words may be interpreted, and it is possible to see this same reasoning behind the concept of Reflection, in which a number of positions and collections have been intentionally left out. Despite this, at first glance it might not be possible to see a connection between the four sections. The first, entitled Construction, opens the book with Baňka’s early photographs from the first half of the 1980s, which use mirrors to “reform” interior spaces, transforming them into impressive optical labyrinths, subsequently followed by studio portraits and nudes. The purely chronological perspective is, however, sometimes interrupted by shots from more recent years, thus indicating that the key to a deeper understanding of the concept behind the book must be sought at a different level. Unvoiced but most likely is the multiple interpretation of the term “reflection”. In the sense of the mirroring of light, it corresponds with Baňka’s sensual approach to perceiving space in his frst mirrored interiors. Later, however, “reflection” is conceived more metaphorically – as the contemplation of the photographic medium (in the section entitled Abstraction) or as looking back at personal history and memories, where this supposition is supported in the Epilogue, which comes across as an album of impressions, excerpts from other series, supplements, and family photographs.

It is particularly through the concluding section that we are able to return to many portraits and nudes from the 1980s and 1990s that are published in the section Figuration. From the perspective of the formal contents, we will certainly most value the (for that time) innovative approach to Postmodernist arranged photography, represented in our country primarily by the Slovak New Wave, or perhaps the older legacy left behind by the photographer and mystic František Drtikol. On the other hand, it will not escape our attention that the figures in these photos are the artist’s wife, daughter, and a small group of models, all of whom played a certain role in the photographer’s creative life other than that of being the most accessible subjects. Of signifcance is the inclusion of the photo entitled Self-Portrait with a Lady from Father’s Desk (1993), in which Baňka’s subtle eroticism and sensuality is closely linked to the powerful theme of father-son relationships. Thanks to allusions such as this, Reflection ceases being the observation of general artistic themes and solutions, and starts to appear as a very personal narrative, the intimate nature of which cannot, in principle, be fully grasped by any external observer. No less importantly, even Baňka’s occasional slide towards a quasi-poetic wordplay may, in this case, be understood as a sentimental expression of the emotional period of Baňka’s well-developed optically creative talent.

Another aspect that we must not allow to escape us is the interweaving of the fascination with elegance and the flawless technological approach with visible links to painting. Looking at it from the long history of artistic forms, this could be a painted portrait, which helped to form the powerful visualization in the artist’s initial works (Figuration), or the existing tension between the depictable and non-depictable boundaries of images (Abstraction), where the relationship to painting is highlighted many times by the concept of “an image within an image” as a “hanging painting in a photograph”.

Most probably we will not fnd a comprehensive answer regarding Pavel Baňka’s position in Czech photography until all three volumes are published. Reflection presents the photographer’s intimate beginnings, where he is fully captivated by sensual reality, which naturally includes the visual richness of the photographic image. A low level of interest in action and social reality is certainly the result of the fact that the book has been limited to include series that Baňka chose according to a more intimate criterion from primarily studio works. However, when he does expose at least a part of himself for observation, the most dominant features are, firstly, his captivation with seeing as a strong source of emotions, and, secondly, the intensifcation of the relationship between sense and sensuality, which may take place within aesthetic contemplation (Construction and Abstraction), or in relation to theme (Figuration). There is some “impurity” in Baňka’s approach, specifcally in the form of the tension existing between his selection of general themes and the inseparable, although more or less apparent, personal motivations to take photographs (and also to include them in a self-constituted monograph). Baňka’s position thus appears primarily as a “task”, serving to interconnect these strengths living in him and to fnd a way to articulate them within the photographic medium, which he however views more as a creative medium than a recording one. As a result, in his hands photographs return to their roots – this time free of any feelings of inferiority. It just is necessary to add that it is also to Baňka’s credit that Czech photography overall has easily shifted towards this concept.

Jiří Ptáček

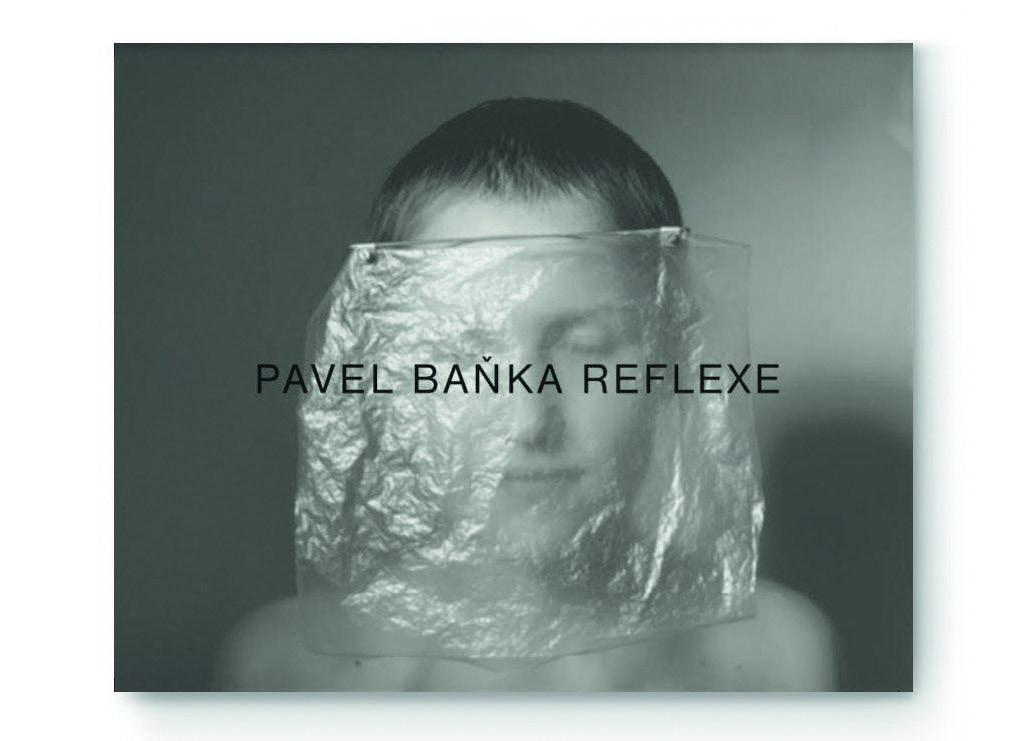

Baňka, Pavel. Reflexe/Reflection. Prague: Artmap, 2016. Print., co-edition published in cooperation with the Faculty of Art and Design of the Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem, 2016. Print.

#29 contemplation

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face