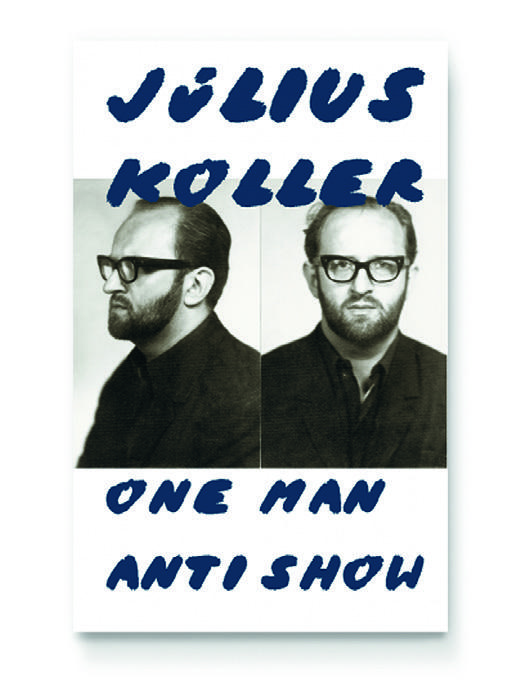

Július Koller – One Man Anti Show

Should we want to show the shift in the interpretation of at Július Koller’s works that occurred at his retrospective exhibition at the mumok – museum of modern art – in Vienna this year, we would have to compare it with this Slovak artist’s breakthrough exhibition, which was held in 2003 in the gallery space of the Kölnischer Kunstverein. Although the same duo of Austrian curators and theorists – Kathrin Rhomberg a Georg Schöllhammer – played a role in both exhibitions, their Slovak partner was different. Whilst fourteen years ago, the artist Roman Ondák acted as curator, this year’s retrospective of Koller’s work was prepared by art historian Daniel Grúň working in collaboration with the two Austrians. We could say that the exhibition in Cologne had the objective of viewing Koller’s works as somewhat of the forerunner to certain tendencies of contemporary art (such as relational aesthetics – a field also represented by Roman Ondák, who had his own solo show at the Kölnischer Kunstverein one year later), whereas this current retrospective defines Koller’s place in art history. The fact that his approaches are different in the two cases is evidenced not only by the institutional framework of the two exhibitions – an art association’s exhibition spaces for the historically first show, and a museum of modern art for the second – but also by the different emphasis found in each of them. As compared to the first one, which was focused almost exclusively on the conceptually oriented photographic documentation of Koller’s “cultural situations”, the current one examines the artist’s work in its entire breadth, and uses a unique method of dealing with the methodological difficulties generally associated with similar projects. Specifically, it refuses to measure Koller’s works against local narratives of local art history or any hegemonic models of Western European or American history of conceptual art. Instead, the curators chose to be guided by the artist’s “self-chronology”, which Koller systematically applied over the course of his artistic career, when the official institutionalization of his works in museums and in art history was denied to him.

The artist’s self-historicizing was fully implemented in the publication prepared to accompany the exhibition. In it, Koller’s works are grouped according to chronologically sequenced concepts, which the artist created and defined himself. Koller placed the start of his work in 1963, when he made his first text pictures – such as his well-known Sea, (1963 – 1964) – which are sometimes associated with formally similar expressions found in American conceptual art, but, as compared to them, lack any self-reflective aspects and are much closer to avant-garde pictograms and calligrams. This is one of the reasons why, in both the exhibition as well as the publication, Koller’s Sea is linked with his small collage Dada Mask, also from 1963, which definitely confirms that the artist was influenced by the interwar avant-garde. Acting in a similarly revisionistic way, the authors of the exhibition, and consequently of the publication, initiate efforts to include Koller’s oeuvre in the history of performance art. They convincingly show that Koller, in his 1965 manifesto Anti-Happening (System of Subjective Objectivity) took on a specific attitude towards happenings as performances turning towards the viewers, when he used his own, often non-artistic activities (such as sports and expressing social attitudes) as the subject of the event. Formally, these “anti-happening” assumed the form of text notifications and photographically documented “events”. However, it is possible to include Koller’s systematic use of the question mark, which Koller started in 1969, as one of their characteristic features. His Universal-Cultural Futurological Operations, (1970–2007) may be considered the apex of this artist’s works. As the authors of the essays printed in the publication convincingly demonstrate, it was specifically during this phase of the artist’s work that Koller fully developed his interest in new forms of communication and overcoming social passivity. This is made obvious primarily in the brief methodological introduction, within which, although it is collectively signed by all three curators, it is possible to decipher the personal inclinations of each of them. It was undoubtedly Daniel Grúň, who, within a later acknowledgement of Koller’s oeuvre, revealed a portent of a “horizontal history of art”, as formulated by his teacher, Piotr Piotrowski, whilst Koller’s specifically East European resistance against commodification as a method of breaking away from the sterotypes of West European art production were evidently more important in the perspectives of Rhomberg and Schöllhammer.

If we consider Koller’s “self-chronology” to be the determinative factor for the publication, then a comparable role in the case of the exhibition design, this role was played by the artist’s archive. In it, art is intermingled with culture, the high with the low, but also includes fetishized artworks with useless waste, which personifies the artist’s ability to create what may be called in-between spaces, which are not only defying unequivocally art-historical categorizations but also rebelling against being embedded in the simple, institutional context of museums. And the exhibition at the mumok strived to achieve something comparable. Similarly like the archive, the exhibition linked taxonomy with chronology, where certain sections were devoted to themes that the artist addressed during various periods of his career, but elsewhere it followed a chronological sequence. Primarily, however, the exhibition, with an ingenious architectural design, consisting of loosely propped up panels, delimited Koller’s works in relation to the museum ideology and left them in something of an in-between space, on the threshold between the public and the private where it was originally created. Maybe specifically because of this that the exhibition emphasized their ongoing topicality. The critical distance that Koller successfully maintained during his entire artistic career is in fact not a thing of the past, but rather – as is more apparent today than at any time before – also a matter of the future.

Karel Císař

Grúň, Daniel, Rhomberg, Kathrin, Schöllhammer, Georg, (ed.). Július Koller. One Man Anti Show. mumok (Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien), Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung König, 2016. Print.

#29 contemplation

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face