Marge Monko

The Chains to Break Free

Gender and class – the two categories of feminist and Marxist theories – have been conflated in Soviet ideology into the hybrid term of a “working mother”: an oxymoron featuring a female figure both submissive and revolutionary, domestic and public, feminine and masculine. By Socialist rearrangement of society, it is assumed that the real “emancipation of women” has already taken place at the moment she is freed from the “petty housework” that “crushes, strangles, stultifies and degrades her, chains her to the kitchen and the nursery”.1 The proclaimed “gender equality” of the Soviet state was a Socialist version of patriarchy where the (traditional) dependence of women on men was replaced by the dependence on the Communist Party, which not only controlled the process of “emancipation”, but made sure its agenda was compliant with the goals of Socialist revolutions. Therefore, the notorious “equality” was in fact nothing but a myth2 – a very convincing and long-lasting illusion that was practically unchallenged in the Soviet period and to a big extent remained unchanged in mainstream post-Soviet discourses.

While a “liberated” Soviet woman was allegedly freed from her “chains” by sharing the traditional women’s duties of babysitting, cooking, washing and ironing the laundry with the State (although the effectiveness of the services was often insufficient), the very core arrangements of the family were not questioned even to the slightest degree. No one expected that some of the “chains” could be placed on men’s shoulders or that any adjustments were needed to prevailing notions of Soviet masculinity. The inherent contradictions of gender politics, where men preserved their authority de jure, while de facto it had been undermined, entailed peculiar gender politics leading to the so-called crisis of masculinity during the late Soviet period. After learning that “gender equality” means a double or even triple workload for women and produces weak and “feminine” men struggling with self-doubt and addictions, the societies affected by the collapse of the Soviet Empire quickly adapted a survival strategy leading to resurrection of traditional gender roles.

In contemporary feminist and Marxist theories, the concepts of gender and class have already been critically re-conceptualized, claiming the need to review the application of these categories and extend their meaning (by inclusion of notions like nationality, age and ability, etc.). A considerable shaking of a gender-class cocktail is also carried out by Marge Monko’s work, where both the interconnection of the terms and their ambiguity is revealed, especially in the context of the post-Soviet society, whose realities are often at odds with theories of Western origin. However, historically neither Marxism nor feminism had ever been an exclusively Western occurrence, rather they became such under the circumstances of the artificial and often manipulative intellectual isolation of Soviet ideology and propaganda. As a result, from the ‘90s onwards, Estonia and many other so-called “Eastern bloc” countries found themselves deprived of theoretical tools to analyse the onset of poverty, exploitation, alienation, sexism and inequality.

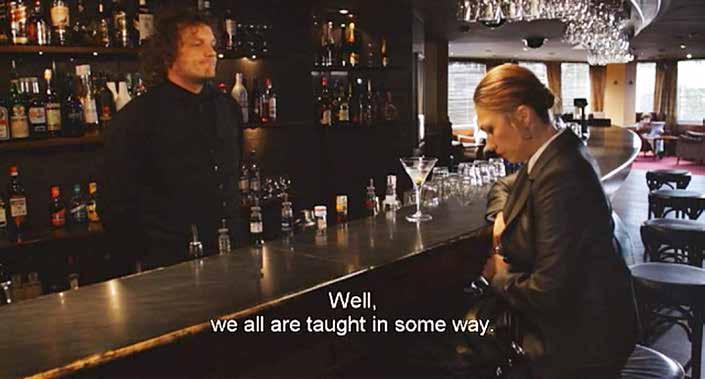

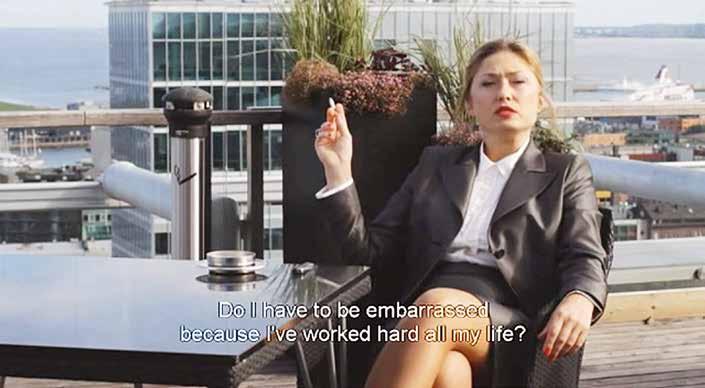

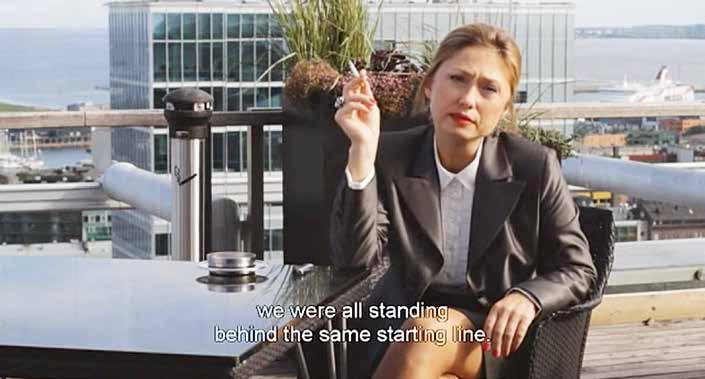

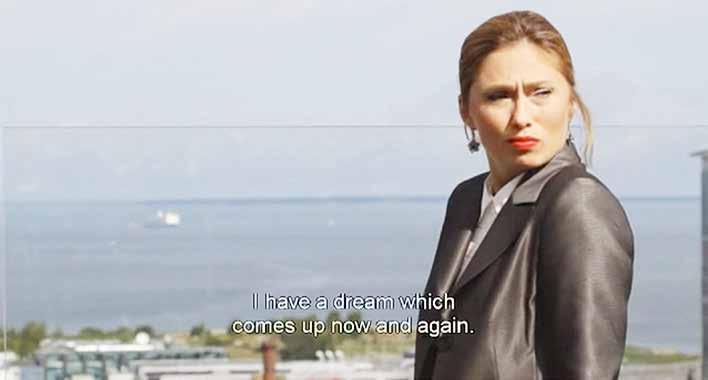

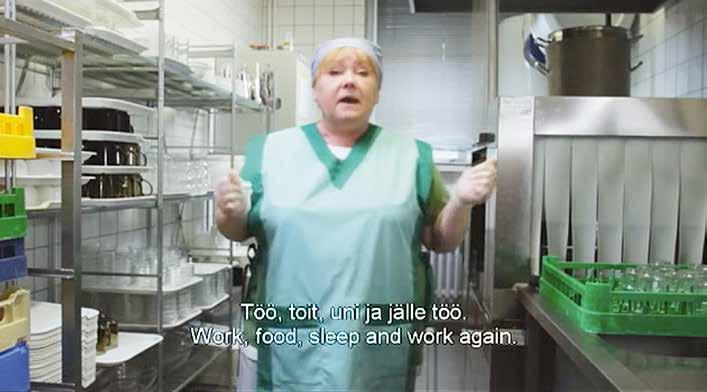

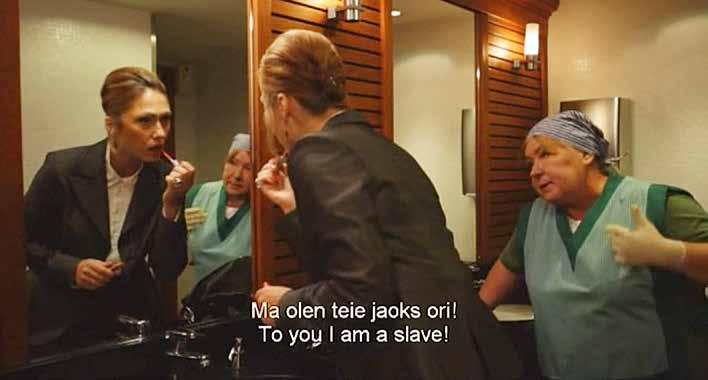

Drawing on the perspectives of three persons occupying a distinct position in the social stratum, the video work highlights their respective peculiarities, privileges and pains. The well-off businesswoman is made vulnerable by her gender role (which includes the sacrifices of motherhood and the sorrow of a lost love life), and her sole remedy for preserving self-dignity seems to be money. In turn, the bartender can always fall back on his chauvinist views and abandon himself to the enjoyment of easy come, easy go money; however, the disturbing feeling of “having achieved nothing” makes him insecure. Finally, there is the elderly Russian-speaking cleaning lady from the underworld of capitalist society, who has already lost everything except for her dream (which is unlikely to come true). However, her low status entailed by her threefold marginalization (as an old Russian-speaking woman) and the bitterness of her life experience means that her accusations are well-grounded and give her the prerogative to make complaints without being silenced and the right to be rude and go unpunished. Which of these three scenarios would seem more appealing and which chains of social injustice are easier to break? The answer is far from obvious.

1 Lenin, V. A Great Beginning. Heroism of the Workers in the Rear. “Communist Subbotniks” // Collected Works, 29, 1965. Moscow: Progress Publishers, p. 429.

2 Voronina, Olga. Soviet Patriarchy: Past and Present // Hypatia, vol. 8, no. 4, 1993, p. 97.

#34 archaeology of euphoria

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face