Some Incriminating Photographs

We asked five personalities to name photograph(s) that they either consider important for the relationship of music and photography (pointing to a particular or typical aspect of the area in question) or to select a photograph which they feel was personally import ant in terms of their own relationship to music. Here’s what we got.

Fred Ritchin

author, curator and critic, Dean of the School at the International Center of Photography

This image, of David Rokeby’s A Very Nervous System, refers to the relationship between image and code and, eventually, music. Cameras photograph Rokeby (or anyone else) moving, and algorithmically translate the image into sound. The subject’s gestures cause different responses, so that people in Rokeby’s System flail around. What I like most about this project, which was first created in the 1980s, is how it raises the issue of photography as a means to making music, not just visually recording someone else making it. In the near future we will undoubtedly see people walking around with cameras while calling themselves musicians.

Quentin Bajac

chief curator of photography, MoMA

Two photos that are for me intimately related to music and to my teenage

years in the very early eighties – a period where I was listening to music a lot and where I now, looking back, realize how the photos and design of the album covers (I am of the vinyl generation) where important for my visual training: the first is the cover of The Clash’s 1979 London Calling album, with Paul Simonon smashing his bass guitar, a blurry image by Pennie Smith that wonderfully encapsulates all the energy of the band’s music; the other is the cover of Eyeless in Gaza’s Caught in Flux, an album released in 1981: an enigmatic black and white anonymous image from the sixties (I often wondered if it was a staged image done especially on purpose or a found snapshot because it has a staged quality in it), that is also indirectly about sound – the deafening sound of the falling water in the background.

Bill Powers

author of Interviews with Artists and owner of Half Gallery, New York

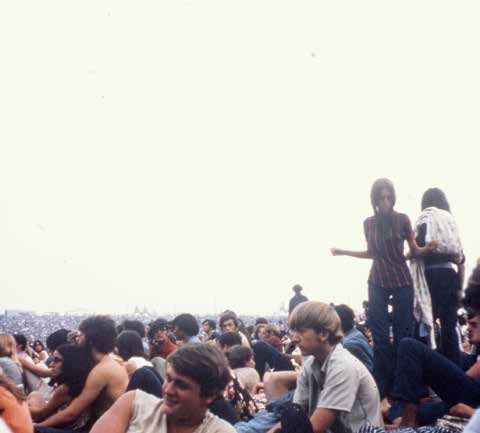

I select Richard Prince’s only photograph he took at Woodstock. Rather than shooting some rock ’n’ roll band, he opted for a crowd shot, which in the end proved more relevant over any particular performance.

Sarah Thornton

author of 33 Artists in 3 Acts, Seven Days in the Art World and Club Cultures:

Music, Media and Subcultural Capital

When I look at Christian Marclay’s Five Unwound Cassette Tapes, I see a waterfall of sound. It is nearly silent at the top, but descends into a noisy, improvisational jazz quintet. The linear, orderly, discreet sensibilities of the five

instruments are subverted when they hit the ground. The hard surface creates a cacophony that is so loud and violent that it becomes difficult to distinguish the clarinet from the bassoon. Even the flute is hard to follow.

This artwork also makes me think about the lost world of old technologies, both visual and musical. The “cyanotype” or “photogram” was developed in 1842, just a few years after the advent of photography, mainly as a means of reproducing diagrams (aka “blueprints”). The cassette tape is an intermediary form, historically sandwiched between vinyl and compact discs (we like to forget about 8-track tapes). Cassettes became popular amongst consumers in the 1970s with car stereos and “ghetto blasters,” hitting a high point just after the 1979 launch of the Sony Walkman, which consolidated its status as the first mobile sound system.

Marclay understands that somehow cyanotypes and cassettes have an affinity. They offer nostalgia along with their obsolescence – something captured in the ghostly quality of the cyanotype’s aesthetics and the gorgeous translucence of cassette tape. Who would have thought that abject, brown magnetic tape could ever appear so beautiful? Every old medium should enjoy such a glorious afterlife.

Vince Aletti

author and critic for The New Yorker, “the first person to write critically about

disco before it had a name (in Rolling Stone in 1973)”.

Hedi Slimane is a music fan – excited, obsessive, smitten. Since 2012, when he was named the creative director and designer for Saint Laurent, he’s used more musicians than models in the advertisements he shoots for the label, including Jerry Lee Lewis, B.B. King, Courtney Love, Daft Punk, and Christopher Owens. But his best photographs feel more like diary entries than formal portraits. Whether he’s focused on the heat of a performance or more casual moments backstage, Slimane’s work always has a sense of intimacy, and a perfect balance of spontaneity and control. This picture of Pete Doherty of Babyshambles in 2004, fucked-up and glamorous in the first flush of fame, is one of Slimane’s most memorable: the ultimate fan’s snapshot turned icon of an age.

#25 popular music

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face