Simon Menner

Images From the Czechoslovak Secret Police

Simon Menner’s photographic practice is concerned with surveillance and pictorial propaganda as the main mechanisms of power in our current conflict-driven times. In the context of post-truth politics, his work feels even more pertinent. Through his photographic projects he dissects various formats of staged and performed realities, and explores the instrumentalisation of images in the era of media-warfare.

In 2011 Menner was granted access for two years to the archives of the former German Democratic Republic’s Ministry for State Security (Stasi) in Berlin. His treatment of the material found there was driven by the idea of ‘showing the act of surveillance from the perspective of the surveillant’. Taken by Stasi agents, inadvertently, the photographs from the archive have an incredibly dead-pan aesthetic, and their reading is rather ambiguous. A case in point is a Polaroid of a Siemens coffee maker from the late 70s, which looks like a predecessor to a one depicted in a black-and-white photograph by contemporary Czech artist Markéta Othová. Her Untitled, undated series is concerned with the impossibility of the photographic interpretation of reality, but it is exactly the ‘interpretation’ of the Stasi Polaroid that is of fatal significance. Taken by a Stasi agent, during a routine secret house search, it could have landed its owners a prison sentence. Possession of such an innocuous household appliance would be noted: it was made in West Germany.

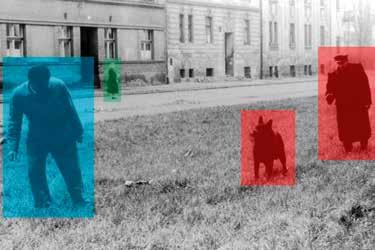

The Czechoslovak State Security (StB) archive in Prague is located near the Goethe Institute, which initiated a joint project in 2015 and invited Menner to spend just over three weeks exploring the material there. Whilst the Stasi archive has been meticulously indexed, annotated and systematized, there was much less information available as to the interpretation of the StB material. The photographs that Menner came across were seemingly self-explanatory, chronicling various exercises and re-enactments of StB operations: staging arrests, learning how to pickpocket, plant compromising materials or follow a suspect.

This raw visual material was of a more straight-forward nature, but there was little information as to the origin and content of the photographs. Perhaps this lack of certainty called for a specific approach, playing with the blurring of lines between fact and fiction (the modus operandi of the Secret Services) and calling out the opacity of our perception.

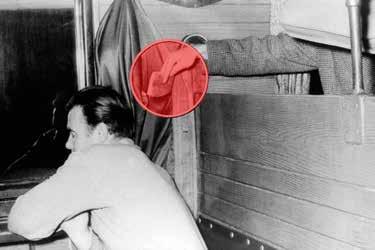

In the Arrests series, Menner colour-coded the various protagonists in a sequence of rehearsed scenarios. In the Pickpocket series, he zoomed in on the details of the hands. Whilst this graphic treatment magnifies and exposes the malevolent practices of the Secret Services, the actual acts that were taking place throughout the society on a daily basis were indeed invisible. It was the consequences that were known.

The distribution of visibility governed by the state recalls the chilling work of the photographic retouchers of Soviet Russia. The new ‘art form’ (which proliferated during the Great Purge of 1936–38), was concerned with banishing the opponents of Stalin’s regime from the image world, to echo their physical eradication. The subjects in photographs and images were being edited out, whether neatly cut out with blades or just blotted out with India ink. One of the most grim and notorious examples of such ‘artistic retouching’ was found in a book designed by none other than the great master of the Russian avant-guard, Alexander Rodchenko. The haunting portrait of Isaak Zelensky, beheaded by a big black blob of ink, comes from Rodchenko’s own copy of Ten Years of Uzbekistan, a beautifully designed commemorative album of a decade of Soviet rule, published in 1934. However, by 1937 Stalin had most of the Uzbek leadership removed or killed. Most were portrayed in the book, and thus Rodchenko took it upon himself to deface his own work. Such was the fear that self-censorship was a matter of survival.1

The StB photographs in Menner’s series, with their absurd compositions and almost comical inauthenticity, date from some twenty years later. And yet, even now, thirty years after the (Velvet) revolution and the fall of the Berlin Wall, they still convey the corrupt feeling of collaboration, mistrust and collective paranoia.

1 King, David; The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia, (1997 ed. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books)

#34 archaeology of euphoria

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face