The Poete Maudit of Photography

Jan Svoboda, born July 27, 1934 in Bohuňovice near Olomouc, died a lonely man in a tenement house in the working class Košíře district of Prague. It was here that he created a substantial part of his oeuvre. He was found dead on January 9, 1990. Official protocols set as the date of his demise the first day of the New Year. The artist did not live to see the completion of the monograph on which he was working with Petr Balajka, but he still would have been able to have a clear idea of it. Although he entrusted a colleague to make the reproductions of prints for publication, he nonetheless took part in the selection process.

The most recent reproductions in both the first, and now recently also the second book dedicated to the artist are dated to 1986. According to his own testimony, Svoboda had started pursuing photography in earnest three decades before. Apart from still life images and the series 100 Views of the Michle Gas Works / 100 pohledů na michelskou plynárnu presented as sober two-page spreads, his earliest artefacts include portraits of his artist friends omitted by both books. Svoboda regarded himself as one of them, and made photographic reproductions of their work. He thus simultaneously used photography both as an auxiliary medium and as a medium of his own self-expression. Throughout his entire life he struggled with the same underrating of the metaphysical qualities of his work as did other artists working in the medium of photography.

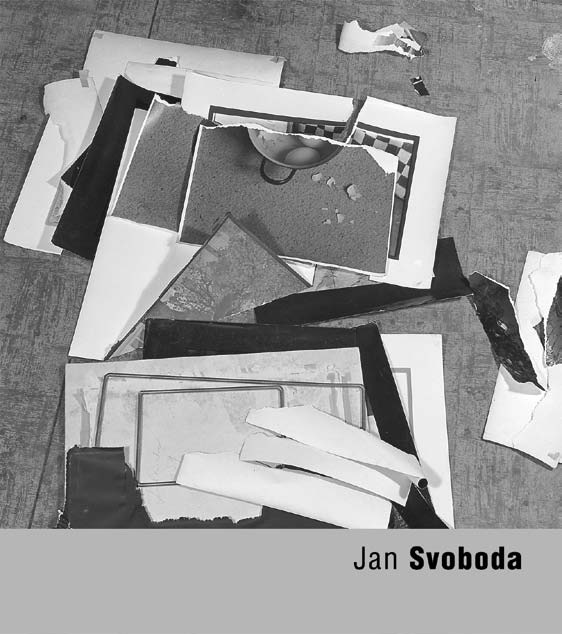

The second monograph dedicated to Jan Svoboda likewise bears the his name as the sole title; both the accompanying essay and the selection of photographs are the work of Pavel Vančát. The latter has already presented his perspective on Svoboda‘s legacy in short form in Fotograf #4 (2004) as well as having curated a small installation dedicated to Svoboda for the Josef Sudek Studio (2006). Vančát has a number of predecessors in terms of multi-faceted interpretations of Jan Svoboda: these are cited in well-chosen quotations and references which attest to his thorough knowledge of the issue at hand while also avoiding deluging the reader with unnecessary detail. The present review is not the place to provide a more detailed recapitulation; a most useful survey of Svoboda´s achievements as an artist is provided by Vančát‘s own essay. I will therefore accentuate only an extreme moment. The re-evaluation of the artist as a post-Modernist (Antonín Dufek) has been widely accepted and is now undergoing a certain shift. While Svoboda repeatedly challenged tradition, emphasizing his childhood spent in a Moravian village as well as the rural sources of his inspiration, the motto of Vančát‘s book as cited on the cover places him “among the world’s pioneers of photographic appropriation and the forerunners of conceptual photography.” Well, each interpreter is on a quest to discover his own reading of Svoboda. Perhaps even at the cost of a misunderstanding. To most viewers, however, Jan Svoboda‘s photographs (particularly) of his work desk evoke the spirit of Cézanne‘s rendering of Mt. Sainte-Victoire. That is to say, of intuition, and not something undertaken á la these. Why, do not images became merely illustrative once we have grasped the underlying concept? Does not looking at a conceptual series inspire a sense of overwhelming tedium more than anything? Is there perhaps more inspiration in the unfathomable after all? And therefore isn‘t Vančát‘s shift in his re-reading of Svoboda perhaps counterproductive? Even the author himself in fact suggests the possibility that Svoboda‘s captions Twenty-Third Photograph After Josef Sudek / Dvacátá třetí fotografie podle Josefa Sudka (1970) and Seventy-Second Photograph After Josef Sudek / Sedmdesátá druhá fotografie podle Josefa Sudka (1973) indicate a reference to a fictitious cycle – that is, a sense of detachment rather than adherence.

Should Svoboda ever receive a more representative monograph, it ought to be more comprehensive as well as more generous in terms of format. Out of the 92 photographs in the present publication, a dozen date to the 1980s, and one-tenth of them to the 1950s. This outline defines as the focus of Svoboda‘s oeuvre the 1960s and 1970s. The full effect of Svoboda‘s photographs is achieved by a most precise toning of the transitions between the tonal values of grey – an extremely daunting task in terms of the demands required by the printing. In the first monograph, the printers resigned on this outright. The second book opted for the solution of scanning the negatives. In the future, digitalisation of the original prints should be given preference, at least where the photographer has signed and dated the prints. For these inscriptions provide a sort of finishing touch to the image. Vančát is naturally aware of this fact, even referring to it in his essay, and reproducing the print of The Other Side of Photograph / Druhá strana fotografie (1969) from the collection of the Moravian Gallery in Brno. The first monograph published the same photograph without the artist‘s inscription and comparison shows that in Svoboda‘s case the handiwork touch is all but indispensable. Another significant factor is the format of his prints; in an editorial note Vančát apologises for omitting to provide information regarding format in some cases where the data was unavailable. Although as a rule the data is not missing, nevertheless the scans of the negatives could not be checked with works from museum depositories. This discrepancy can be showcased by the case of Melancholy / Melancholie (1963) as reproduced by Fotograf, with regard to the original. A connoisseur will be haunted by this comparison every time they browse through the 37th volume of the Fototorst edition; this compromise was nonetheless economical in nature. The current Jan Svoboda monograph received the support of the Czech Ministry of Culture and would scarcely have been able to come out without this subsidy, as Svoboda‘s work offers contemplation of art and the medium of photography rather than a treatment of popular motifs. This year has been marked by the rise in VAT (not only) in the area of book culture, and the publisher Viktor Stoilov does not plan to bring out a volume 38 in 2012. Thus far 2013 remains open.

Josef Moucha

Pavel Vančát: Jan Svoboda. Prague, Torst 2011.

#19 Film

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face