Evokativ

In the spring of 2018, the Association of Professional Photographers of the Czech Republic named Libuše Jarcovjáková (born 1952) personality of the year.

She was nominated for the award by Jan H. Vitvar, cultural editor at Respekt magazine, in respect to the publication of her journal-memoir Černé roky (Black Years). However, his justification could also be applied to Evokativ, the album under review: “Libuše Jarcovjáková, creating at the edges of both the art scene and society, has shown herself to be one of the most important figures in the history of Czech photography. This is not an overstatement. Her prerevolution work has no local equals in its intensity, honesty, and energy, and in many respects surpasses the international photographers whose work has been taught at universities for decades.”

This new book was published to accompany a retrospective attached to the Rencontres d’Arles 2019 festival. The British daily The Guardian declared Evokativ the exhibition of the year. This dual event is rightly considered a suggestive reckoning of

the 1970s and 1980s. It captured the visual core of how the photographer lived. (As for words, the author limited herself only to a succinct summary of her memories.)

Although Jarcovjáková’s life in her native Prague was a hellish spiral of hopelessness, she managed to graduate from the photography department at FAMU. I borrowed her diploma opus on Robert Frank and read it with interest. It is no accident that what I find in her notes is what inspired and captivated her about Frank: “He stopped showing pictures and started showing emotions. With that, he opened a new space in photography.”

For Jarcovjáková, gradually publishing her observations at the time these were made was unthinkable. Certainly not in the clearly delineated selection which is now receiving such accolades. The photographer would have unmasked the people in her snapshots. And she also would have become a dangerous snitch. This was, after all, a time of Communist rule—rule reinforced by various repressive bodies including the secret police, which was certainly not above blackmail. Jarcovjáková, then, was chiefly shooting pictures for herself. Perhaps as memories but definitely with a passion bordering on obsession. She told Reportér magazine that she had negatives of every phase of her daily parties: “Going out, sitting in the pub, coming back home.”

The editor of Evokativ is Lucie Černá: she determined the order of the reproductions, connected the optics of the exhibition into a narrative of images, and wrote the epilogue. Perhaps only those who have gone through such an ordeal can suspect what lurks behind the austere information in the masthead. A superb performance, I’d say! This first production by a new publisher, Untitled, clocks in at 188 pages in a representative 210 × 275 mm format. The language chosen is English. The graphic design was both functionally and aestheti- cally prepared by Ania Nałęcka-Milach.

The epilogue (and the publisher’s blurb) promote Evokativ as an authentic document of the artist’s life. The whirl of the nights in the metropolis, casual relationships, and alcoholic and sexual excesses are captured without aesthetic calculation and without concern for badly framed shots. A significant element is the overexposure of the foreground through copious use of flash. Supposedly, it represents a personal style based on a combination of raw non-embellishment with a poetic quality. The pictorial composition, however, is arranged from positions of hindsight, which are therefore informed by the directness which users of photography often employ today. Images like these, which alternate with improvised self-portraits, are now made by every Tom, Dick, and Harry, but the newly discovered classic Libuše Jarcovjáková has her inexhaustibly loaded and irreplaceable past.

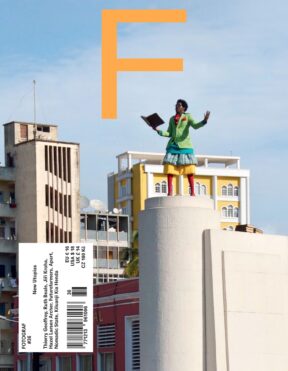

#36 new utopias

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face