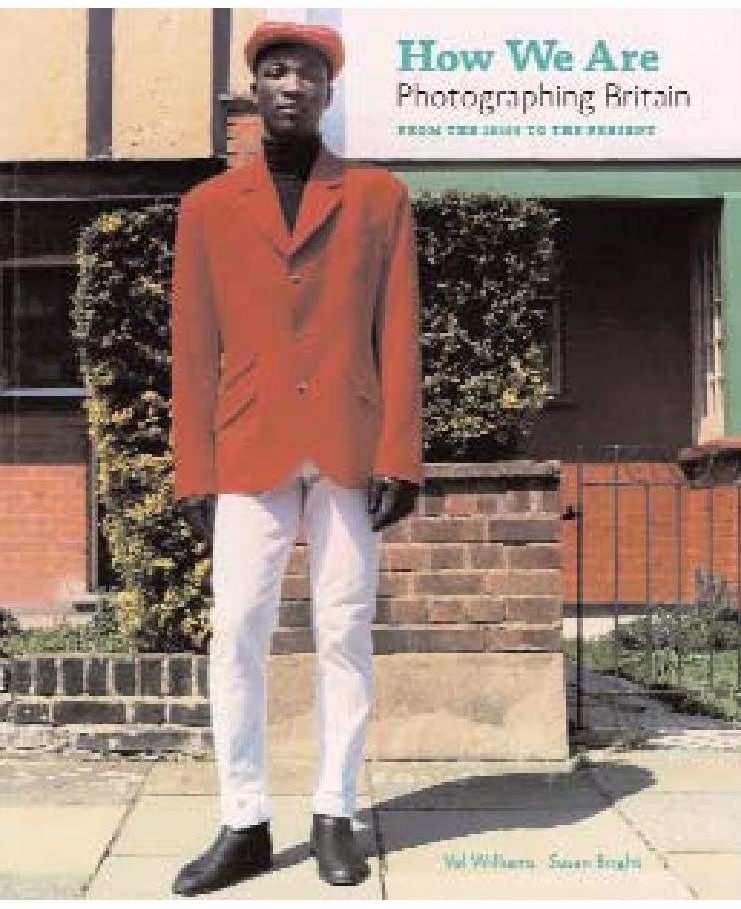

How We Are: Photographing Britain from the 1840s to the Present

Curated by Val Williams and Susan Bright; Tate Britain, London, 22. 5. – 2. 9. 2007

Quite logically, the first major photographic exhibition at London’s Tate Britain was devoted to British photography. However, the objective of curators Val Williams and Susan Bright was not to create a definite historical overview, but rather to break through certain rigid boundaries of interpretation. They succeeded in expanding the seemingly closed set of big names by looking at photography as part of the broader field of visual culture. This conception led the curators to places other than just the collections of renowned museums, to unstudied archives such as the Antony Wallace Collection of the British Association of Plastic Surgeons or the Barnado’s Archive in London’s East End.

A determining factor in the curators’ work was an attempt to capture and describe the essence of British national identity using the works of the photographically active part of the British population. One of the exhibit’s theoretical pillars was the thinking of Benedict Anderson, who in his book Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (first published in 1983) discusses so-called shared mental maps which increase our sense of belonging to a specific nation. For this reason, “How We Are” included not only selected works from the realm of art photography, but also family albums, medical photography, advertising and propaganda photography, postcards and documentary photography, among other genres. Familiar works by 19th-century British photographers such as William Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins, Roger Fenton, Julia Margaret Cameron and Peter Henry Emerson were thus hung next to Hugh Diamond’s remarkably unsettling portraits of mentally ill patients or works from the archive of photographs of working women created by Arthur J. Munby. Not far from the works of Alvin Langdon Coburn, Madame Yevonde and Cecil Beaton, one could literally discover Percy Hennell’s photographs of wounded Second World War soldiers following plastic surgery, or photographs of “well-known militant suffragettes” from police files. Nor did advertising photographs from cooking magazines, the National Rose Society’s Annual or postcards by unknown photographers escape the curators’ attention.

In and of itself, looking at the history of photography within the broader context of visual culture is hardly an isolated phenomenon nowadays (a similar approach was chosen locally by Pavel Vančát and Jan Freiberg for the recent exhibition “Czechoslovak Photography of the 1970s”). Nevertheless, it is worth reflecting on the fact that an exhibition at an institution such as the Tate Gallery included genres (such as amateur photography) which previously had been only of peripheral interest to most curators or art historians. This phenomenon is partially related to the democratisation of the photographic medium, which – with the advance of digital technology – has definitely ceased to belong to a narrow group of people. In the spirit of the sentence “we are all photographers now”, the curators thus even invited the public to participate in shaping the final section of the exhibit, dedicated to contemporary photography. They could do so through the flickr.com website, where anyone could upload his or her photograph on one several subjects: portrait, landscape, documentary, still life. During the final month of the exhibit, a jury (Val Williams, Susan Bright, photographer and co-curator Derek Ridgers, photographer and member of the Flickr team Heather Champ and Greg Whitmore, image editor at the Observer, the exhibition’s media partner) chose ten winning photographs from each category, which could be seen both online and in the museum. The question remains however: Does an exhibition claiming to “liberate” the photographic medium need to name winners and thus also losers?

#10 Eroticon

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face