How to Think About the Theory of Photography in the Czech Context?

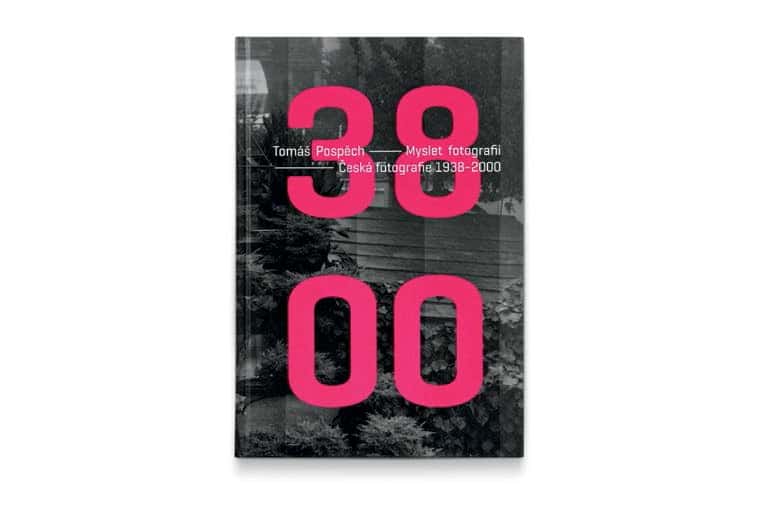

As both a trained art historian and a photographer, Tomáš Pospěch is one of those qualified to “think photography” from both perspectives, from the position of an artist as well as a theorist. To what extent this disposition is more of an advantage than a disadvantage depends on the specific situation and circumstances. In the case at hand, Tomáš Pospěch set himself an ambitious task – writing the historiography of Czech photography between the years 1938–2000. To a large extent, the text draws on his dissertation thesis, which he defended at his alma mater, the Silesian University in Opava, Czech Republic, where he has now for many years also taught at the university‘s Institute of Creative Photography. It should be said right at the outset that his most recent book represents – and surely will do so in the future – a highly valuable source of information. Covering a broad spectrum of themes related to the writing on photography, it also gives attention to hitherto little documented aspects of the history of Czech photography, thus bringing together in one volume a mass of information which had thus far been scattered across newspaper articles and photography monographs. This painstaking effort is a great service to the Czech history and theory of photography, and it should be duly noted that these fields owe a great deal of thanks to Tomáš Pospěch.

In reviewing the present volume, one naturally cannot overlook Pospěch’s previous work, the anthology of Czech photography “in reviews, texts and documents”, covering the same period of time as his more recent book. If my objection to the anthology when it came out was that it left all interpretation of the texts it presented up to the viewer, I must now observe that the introductory essay to the present volume written by Pospěch suffers from no such shortcomings. Although the author suggests at the beginning that his is a critical study, he nonetheless offers the viewer no easy orientation to the “multiple, overlapping discourse.” Interesting thematic areas are only pointed out at the very conclusion, which poses important questions. These, however, remain unanswered. For example, Pospěch suggests a provocative comparison of the relation between photography and art, and the relation of Eastern and Western art history: “Is not the same lack of understanding and unwillingness to see the parallels of Eastern and Western art characteristic also of the approach of contemporary art theorists towards photography? Is not the absence of Central European and East European art – with the exception of Russian art – from European and American art history textbooks a similar phenomenon to the absence of photography in Czech histories of art? How does one revise the paradigm which causes this omission?”

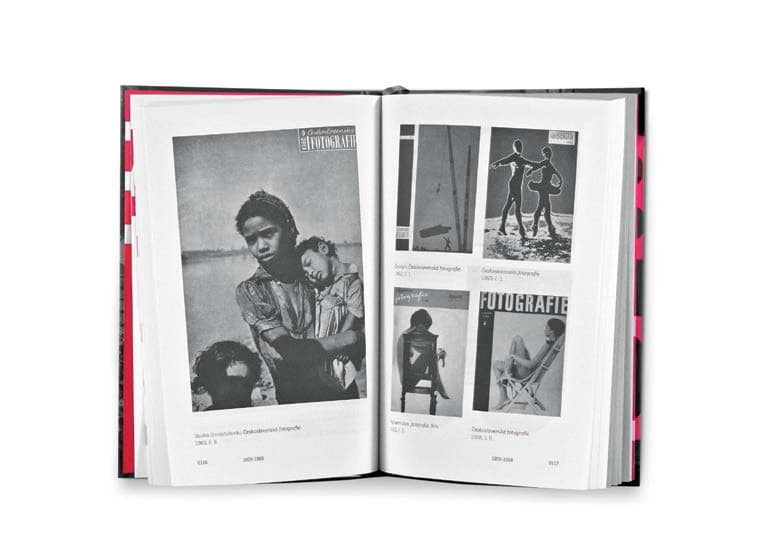

But let us return to the beginning. The opening chapter promises to give a method of observing history “of the modes of abstracting visual reality into notions, and their construction into coherent text”; even an erudite reader, however, struggles to see this. Although Pospěch emphasizes at the outset that his “aim was not to create a chronologically ordered factographic catalogue of published texts on photography”, as I have already pointed out, the outcome is very much just that, and Pospěch’s proclaimed departure from a positivist approach is hardly noticeable in the book. Even his “in-depth analysis of selected case studies” tend towards the objective, bringing forth a great number of facts, presenting little conflict. What is missing is a distinctive position on the part of the author that the reader might reject, or embrace. Vis-a-vis the popularity of the photographic nude, Pospěch offers, that though the human body “may be seen as the vehicle for social, political or gender meanings,” in 1950s Czechoslovakia it was labeled a “vapid, escapist subject devoid of content and ideological significance.” This contradiction is surely interesting, yet Pospěch does not elaborate on this in any way. Thus one may only agree with him in the final paragraph of his book, where he says that “a number of issues merely sketched here deserve a detailed study in their own right at some point in the future.” The book simply retells the story of the writing of the history of Czech photography in chronological order, thus accompanying the anthology published earlier. It would perhaps have been more useful if the two books had come out as one volume, a comprehensive anthology offering a detailed illustration of the issue, which would also include critical commentary. Be that as it may, Pospěch has laid out a solid foundation for the answering the question he posited in the title of the present review – foundations on which it is possible, or in fact necessary, to build on.

#24 seeing is believing

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face