Jindřich Štyrský

Two monographs have been dedicated to the photographic legacy of the painter, set designer, illustrator, poet, collage artist, biographer and art critic Jindřich Štyrský (1899–1942). The earlier of these, Jindřich Štyrský /fotografické dílo/1934–1935 (Jindřich Štyrský /photographic oeuvre/ 1934–1935) featured one hundred illustrations and was brought out in June 1982 for the internal use of the Jazz Section of the Musicians’ Union by the art historian Anna Fárová, at the time banned from publishing, and thus concealed under her mother’s maiden surname, Annette Moussu. In 2001, the Torst publishers’ FotoTorst edition featured (a now sold out) book of similar scope, titled simply with the artist’s name. The volume Jindřich Štyrský, with essays by Karel Srp, included handsomely reproduced examples from the cycles Man with Blinkers (named after a poem by Vítězslav Nezval), Frog Man (named after a fairground attraction), and Parisian Afternoon (named after the circumstances). All of the cycles focus on the Surrealist objet trouvé, so eloquent in its mirage-like nature as to require nothing more than being captured by the camera.

Štyrský’s photography gave rise to an entire archive of inspirations with non-material associations. In this spirit he was assessed by the critic Jan Chaloupka, whose interpretation of Štyrský´s “photo-pictures” was published in his 1936 study of photography in the local Surrealist activities which appeared in the art monthly Volné směry (Free Tendencies): “Once again we find here, that authenticity rendered in the photo-mechanic way achieves results just as suggestive as the most individual creation of an artist’s effort. In other words: place documentary reality alongside with the painterly imagination and you arrive at the paradoxical fact that reality is, thank God, just as poetic and fantastic. I have in mind those of Štyrský’s photographic works in which the random and yet visionary choice of subject matter, in combination with a strict detachment regarding the optic lens, produces works of poetry and dream-like associations.”

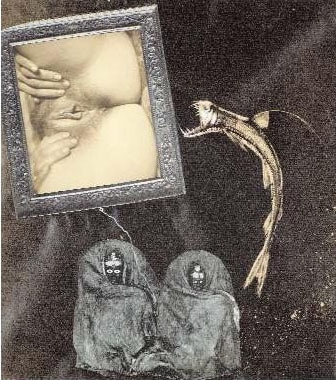

I regard Štyrský’s exclusive solo project, the artist’s book Emilie přichází ke mně ve snu (Emilie Comes to Me in a Dream), as a precious artefact precisely because I am drawn to the stirrings of the mind, rather than obscene anatomies or mindless destructions. The bibliophile edition came out in May 1933, in a print run of 69 numbered and signed copies. In the spring of 1997, New York’s Ubu Gallery sent out illustrated invitations to their exhibition Emilie Comes to Me in a Dream, which also featured the launch of the English-language edition of the book, sealed in an opaque cover of black plastic, with the very visible sticker SEXUALLY EXPLICIT MATERIAL ENCLOSED. The Edition Ubu ran into 1000 copies, while the exclusive limited edition was kept to the cult-like number of 69 copies. The most recent edition was brought out by the Torst publishing house in 2001.

Uncommonly daring in its time was the use of reproductions of pornographic photographs alone. Traditionally, this type of material was dealt with through the means of xylographic reproduction. It was from these images that Štyrský drew in his 1931 work inspired by Vítězslav Nezval’s Sexuálni Nocturno (Sexual Nocturno). The illustrations to the poet’s (not exactly breathtaking) illustrative prose work were set off by drawing on the collages as well as the choice of motifs: he achieved here a similar persiflage as in the case of his own Emilie. The effect, however, is quite different. Between the years 1931 and 1933, when both of the abovementioned bibliophile editions were brought out, Štyrský underwent no surprising turning point in his work. Although in an afterward to his unfinished book Život markýze de Sade (The Life of the Marquis de Sade, published 1995) Lenka Bydžovská cites that a pilgrimage undertaken to the ruins of the nobleman de Sade’s estate in Provence during 1932 inspired Štyrský’s heightened interest in photography, it could also be said that the artist in fact lived up to a program he declared in 1923: “An image must be active, it must do something in the world, interact with the world, with life. In order to perform the task assigned in its surface, it has to be mechanically disseminated […] There will be fewer pictures and more mechanical reproductions. […] The most exquisite poem: a cable, or a photo – economy, truth, succinctness. […] Embrace the new images. […] For melancholy lovers, let us grow black roses.”

Today, many more novices of art are well disposed towards prefabricated material than Štyrský found among his contemporaries, regarding himself as he did as “the precursor of those, who in the fin de si´ecle will flee this century.” Many indeed adopted the model disseminated in the 1920s by the circles around Prague’s Devětsil Group, of which Štyrský was a member. He helped popularize the method of encoding through photographic signs, pasting within the picture reproductions rather than handmade parts both in his visual poems (after 1923) and in his theoretical writing. Here is one of his utterances, so familiar to us today: “Everything in the world has been said and depicted, therefore we cannot build on causes, but on consequences.”

A contemporary poetic is rendered original only by the imaginativeness of finding the subject matter, the ways in which it is dissected and juxtaposed into new entities. This is also a clue to the driving forces that gave rise to collage. Štyrský probably developed the furthest those impulses that undermine eroticism, as laughter gets along with eroticism so poorly, representing as it does within the realm of sex a greater taboo than pornography. He published in 1924 in the first issue of the Devětsil publication Pásmo something akin to a programmatic statement (in his poem Alkohol a růže – Alcohol and Roses): “Yesterday needed art as a diversion / the present needs poetry to be able to find pleasure in life.” In the dreamlike Emilie, duly crackling with paper, he plays a blasphemous joke – much in the spirit of his resolution – on the inhuman dimensions of the metaphysics of space.

These ten photo-collages, accompanied by short somnambulist prose poems, were inspired by cut-outs from periodicals, for the most part from foreign materials imported to Prague from abroad. No matter how much the artist may have announced a powerfully erotic “cycle at the center of which lies the peak of ecstasy”, he did not promise his subscribers true delight, but instead an “involuntary smile.”

Even so, the print run could not be sold publicly, and it was officially banned from public libraries. It was probably why Štyrský did not even exhibit these collages. He distanced himself from pornography both through the inclusion of a pseudo-scholarly epilogue by Bohuslav Brouk and a publisher’s fly-leaf disclaiming pornography as inspiring “invariably nothing but a sense of shame and repulsion.” Naturally Štyrský was no pornographer, and of course he was well aware of this. He had a clear argument, which he voiced on April 9, 1924 in a lecture at the Masaryk University in Brno: “A picture is a poetic vision of the world. A picture can never be realistic, even though it is made from reality and real elements. It can never be illusionist, for we weave in its abstract web concrete lyrical visions.”

#10 Eroticon

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face