Marcos López

a broadside ballad for fallen heroes

In one of his essays on the heterogeneous identity of Latin America, the Cuban critic and curator Gerardo Mosauera broods over the local transformation of circulating signs, citing as an example the metamorphoses undergone by one of the pillars of American popular culture, the Coca-Cola soft drink: a famous mixed drinks recipe decrees that it be mixed with Cuban rum, a slice of lemon and ice. It is significant that the drink known worldwide as Cuba Libre (Free Cuba) is called “Mentirita” in Cuba – i.e., a merciful, “white” lie. Thus while drinking in European bars this cocktail evokes attractive but vague images of a Cuban revolutionary atmosphere, while the island’s bartenders may be mixing into it a few drops of melancholy bitterness.

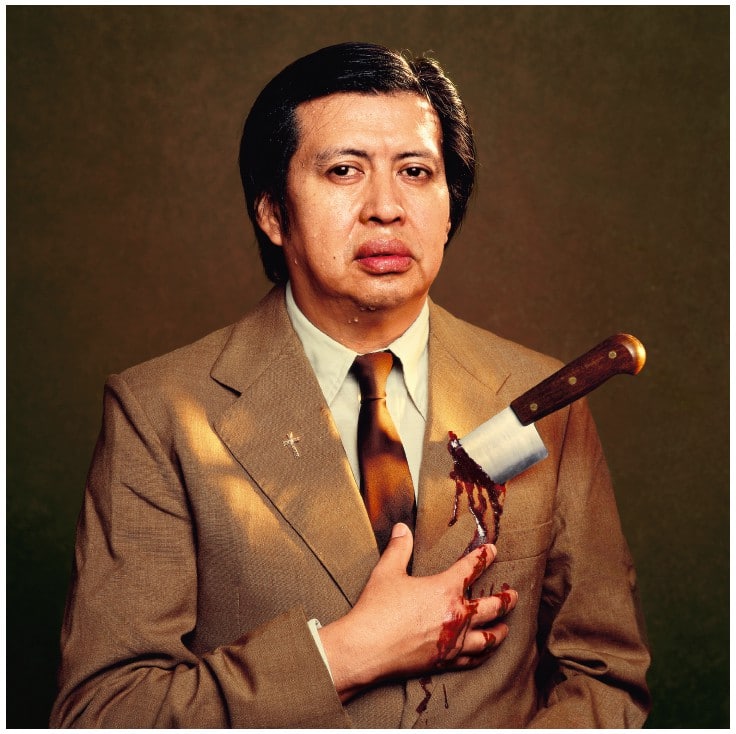

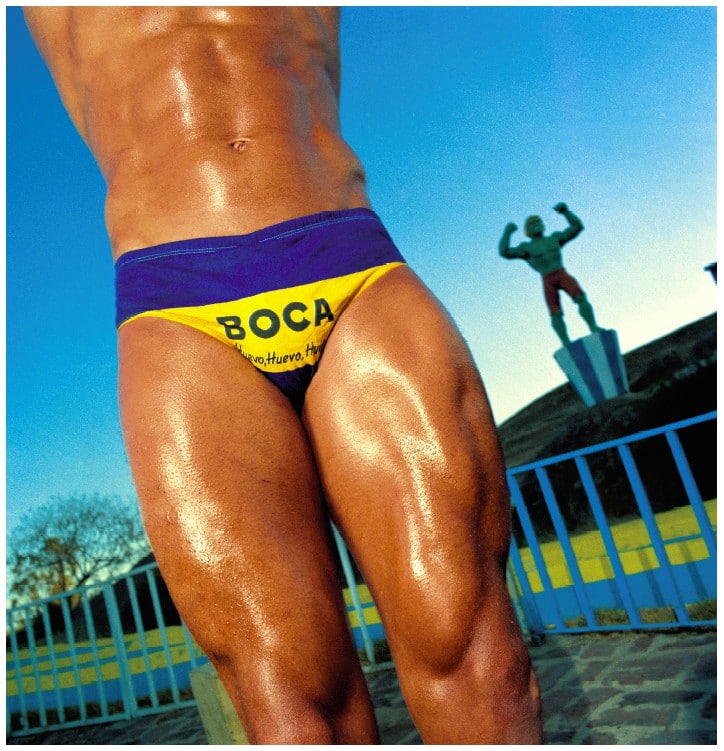

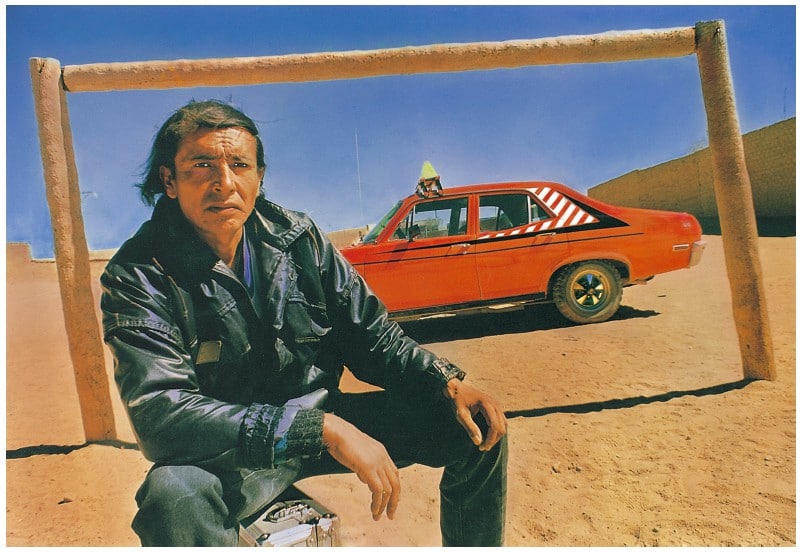

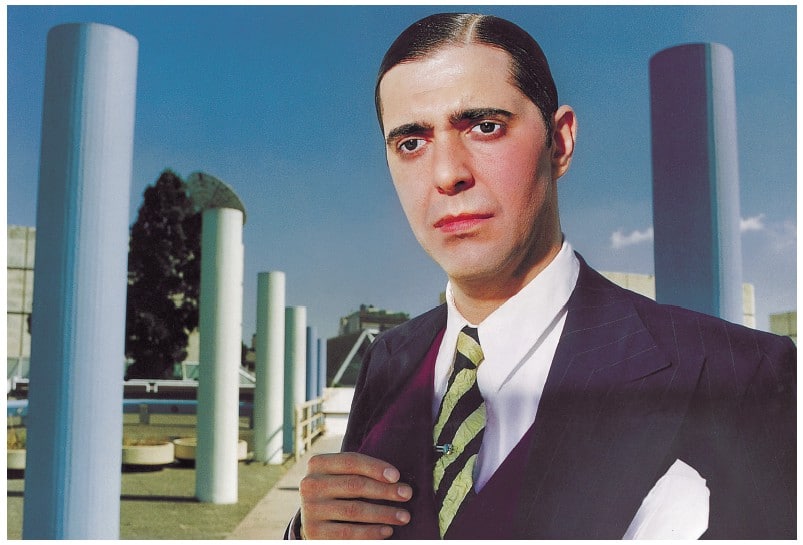

If we take a close look at the faces in Marcos López’s photographs we find that the crankily ironic grin that we see in many figures in reality refers to the immense emptiness of lost illusions. Persons situated in the bizarrely colorful universe of glossed up cars, palm beaches or television studios carry the parody of billboard concepts of happiness to the limits of one’s endurance. Each detail of this world helps the creation of a lurid and deformed illusion of earthly paradise. The illusion, once fed by the imagination of European sailors, has after several centuries turned into a broadside ballad sung by powdered fops, Indian taxi drivers and busy housewives.

Marcos López comes from the small town of Santa Fé in Argentina (b. 1958), but his desire to dedicate himself to photography drove him at the beginning of the 1980s to the coast, to the metropolis. He soon abandoned black and white photography – his beginnings were in portraits of a classical cut, with wide-angle shots of people against a landscape – and started using color, as he says, partly because color helped him to better cope with his melancholic tendencies. The aesthetizing and psychologizing tradition of photographic documentary was followed by a Pop-Art distancing: from now on the seriousness of message is covered up by a jocular arrangement. The human figures remained, but their environment underwent a radical change – its unreal, staged character was exaggerated and emphasized. López admits that his attitude towards creating photographs is analogous to the attitude of a PR agency employee (in fact, he worked for a PR agency for a time): he makes up his models before the shoot – often using professional actors – and carefully arranges all details of dress, creating props for the backdrop. Playacting, the main theme of López’s work, is thus contained in the very first, preliminary stages of the creative process. His tendency towards a pictorial, painter-like attitude is reflected in subsequent manipulations, when the photographs are colored by hand, often printed on paper in a larger than life poster format. The final impression of these surreal collages, populated by mannequins with unnaturally pink cheeks, may perhaps really remind one of the huge frescoes of the Mexican Muralists, whose follower in the “digital nineties” López called himself.

This gradually growing series of color photographs came to be called Pop Latino around 1993, when the Andy Goldstein Foundation award

allowed López to publish his first book of portraits. In the subsequent book of the name from 2000, López draws attention to the audial

similarity of “pop” with the onomatopoeic “plop”, evoking an explosion. He thus admits to a fascination with the language of the comic book, visible in the shorthand of López’s mise-en-scene and in the exaggerated gesticulation of his figures. The full text of the book (the complete title is Pop Latino. Fotografías y textos de Marcos López) is a rumination on the Argentine fiesta, that ambiguous feast of the Latin Americans, for which we find no equivalent in other languages. The Mexican poet Octavio Paz in fact elevates the fiesta to the status of an art form, consisting in the sudden revelation of the unusual: “Fiesta is thus not mere excess, a ritual of the waste of goods painfully gathered throughout the entire year; it is also a rebellion, a sudden eruption in the formlessness, in pure life. Through the fiesta, society liberates itself from the norms it had set itself. It laughs at its gods, its principles and its laws: it refutes itself.” López’s photographs bring out rather the dark side of the fiesta, which consists in pretending at something that one is not, acting out, searching for various disguises as a defense against both the world and oneself.

This is in fact manifested by the figures in López’s photographs, they are no longer even actors acting out their parts, but rather mere paper

mannequins, dressed up by someone who then stuck them against a colorful background. They may be the old man with a red shirt and

sunglasses, a cigarette and a resigned expression, standing at the edge of the road in front of some kind of advertisement for food products

promising the taste of life (Criollitas, 1996). They may be the tanned man with his hands on the stirring wheel of a car with a strikingly red interior,

set somewhere at the beach (Taxi Driver, 1996), or the young man leaning against a glossy car, gazing behind his sunglasses into the distance against the background of a dramatic cloudy sky (Cuban Taxi Driver, 1997). López’s figures’ common feature is their positioning in the foreground, their puppet-like attitude and the scale of expressions, limited to a fixed stare or an unnatural affectation. They give one an ambitious impression, oscillating between amusement and annoyance at the exaggerated artificiality. In López’s panopticum we can find variations on several favorite types – the talk show host, taxi driver, dandy, waiter, tramp, housewife. The urbane figure of Gardel appears several times, once in a flock of laughing schoolgirls (Gardel Appears at a Picnic, 1997), then with a pensive expression in a suburban colonnade (Gardel in Thought, 1997). In one picture the torso of a waiter – the head is cut off by the top of the frame – serves Coca-Cola on a tray, in ruins. Another torso, this time of a bulky man in a US flag undershirt, stands against a background of painted posters featuring Ché Guevara (La Habana, 1997).

López’s own likening of his work to that of the Mexican Muralists is not inadequate: besides the poster size and rich production values incorporating elements of contemporary popular culture, there is similarity also in the socially critical subtext. But while the Muralist movement declared a refreshing return to local traditions, to López all “national” symbols enabling a dubious identification in the name of “La Patria” have lost their meaning and have turned into dangerous clichés, used for the most part merely as tools of power. López’s photographs parody the local implants of international commercial products, but they also deride the traditional concept of Argentina as the country of mathé, of popular tradition, domestic altars, cacti and barbaric gangsters: in Botanical Gardens (1993) a figure with the mask of a laughing, bearded terrorist and a painted revolver jumps out of dense foliage.

The frequent use of sloganeering banners, various masks, mirrors and colored glasses refers to the carnival atmosphere characteristic of the big cities of Latin America – at least to the outsider’s imagination. López’s series Pop Latino in fact started off as a survey of the Buenos Aires city scape (where the author has lived since 1982): the series subtitled City of Merriment was created as a reaction to the political situation of the time. Collages populated with broad smiles, overflowing with the merry slogans of the presidential candidate, they are a farcical representation of the populist politics of Argentina’s then-president Carlos Menem, whose lofty promises announcing Argentina’s triumphant entry among the countries of the “first world” ended in economic crisis. From Buenos Aires, López’s criticism moved to Latin America in general, for whom the recycling of world symbols and the transgressive subversion of values becomes a defense strategy to survive on the margins of interest, in the space of unfulfilled promises.

Finally Jorge Luis Borgés appears in the stream of López‘s characters – the famous black and white photograph of the writer with his eyes closed is lifted by a hand against the background of a kitschy pink castle in the vicinity of an averted equestrian statue of a warrior pointing into the distance. Are the painfully closed eyes of the philosopher suggesting that the phantasmagoria of his homeland can only be faced by an escape into the merciful lie of the unconsciousness? The veneer of triumphing merriment has cracked, and, “as always, the fiesta is tinged with bitterness.”

#3 Transforming of Symbols

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face