Not only about the Model’s Dirty Feet in the photo by Christopher Williams

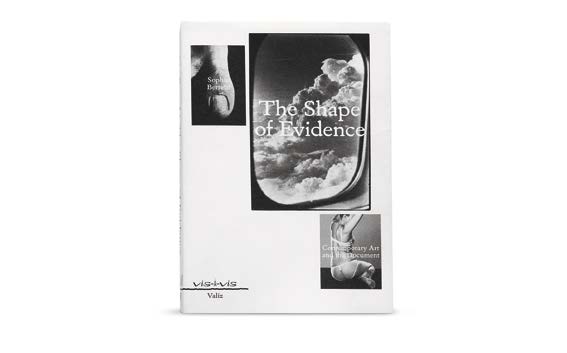

Sophie Berrebi begins her book by mentioning her own parents and grandparents. We learn, amongst other things, that her maternal grandmother completed her dissertation under Roland Barthes and, more importantly, that she owned a Citroen model that is immortalised in Barthes’ collection of essays Mythologies. Although a bit of an overstatement, given the topic of this issue of our magazine, it is certainly the most important piece of information we will obtain from the reviewed book. Although Berrebi refers to Barthes and his thesis regarding the evidentiary power of photographs even in the title of her book, she also draws attention to the fact that this thesis must be applied critically (‘there is nothing evident about evidence’) and prefers to write about the possible ‘shapes’ this evidentiary power may take. She looks at the artists associated with the documentary turn that took place during the last decade of the 20th century and the start of the 21st century, discusses the history of documentary art with primary emphasis placed on the process by which power is fabricated (‘a document is never accidentally found, but in reality always knowingly constructed’), and finally, focusing on the given topic, analyses the shift from analogue to digital technology. She applies synthetic analysis and, from addressing specific works, reaches a level of more general classification that resulted in the book being divided into four chapters. The first is concerned with the works of Jean-Luc Moulène. Berrebi places his photos of statues into historical context and points out the functional level of photographic documents as they are used to reproduce works of art. The second chapter looks at the works of Zoe Leonard. The author draws attention to how a photographic document may be used to provide ‘objective’ information, for scientific purposes for example. In the third chapter, using selected works by Christopher Williams as an example, Berrebi points out, amongst other things, the role that text plays in photography, on its readability and its links with industry. The fourth section is focused on the artistic use of archives as an instrument of power and for the ‘decolonising of documents’.

In the short epilogue we find out that, although each of the chapters is focused on a certain selection of works, there are several fundamental themes that are interwoven throughout the entire book. These describe: 1) the phenomenon of a work of art as a document in the broader sense of the word than described by the ‘documentary turn’ in art at the break of the new millennium; 2) museum and archival systems and the resulting processes for sorting information; 3) the way in which our thinking forms a scientific ‘objective requirement’; and 4) the paradox of the digital age, consisting of the nonstop transformation of information into data, which Sophie Berrebi describes as ‘amnesic recording’. The book is thus an accurate reflection of the research that has been performed in the field of photography, documents and art, and, although it does not present any innovative paradigm, I strongly recommend it to anyone who is interested in this topic.

#27 cars

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face