Nico Alexandroff, Robert Zhao Renhui, Susan Schuppli

Between Before and After

The artistic practices of Nico Alexandroff, Robert Zhao Renhui and Susan Schuppli, where glacial sampling and analysis exist alongside the photographic, are presented together, where they have formed into something synthetic, something not yet clear but deeply promising in their capacity to perform multiple functions at once. Together, Alexandroff, Zhao Renhui and Schuppli’s work communicate the complexity of bodied planetary experience, its consequences, and the increasing urgency of phenomena that used to exist outside human timescales but can now be captured — and responded to — in the scale of the now.

“The knowledge of future things is, in a word, identical with that of the present.” Plotinus, Enneads IV.121

On August 14 and 15, 2021, air temperatures at the highest point of the Greenland Ice Sheet2 remained above freezing for somewhere around nine hours. What happened next was an unprecedented event in recorded human history: the clouds released rain onto the ice sheet. Scientists observing the event had no gauges to measure the rainfall because it was so unexpected. The surficial snow melted, seeping down into the layer of compacted snow, not yet glacial ice. As I type this, this meltwater is now forming into a hard surface — an ice lens — through which any future meltwater will not be able to penetrate. This ice lens will amplify a feedback loop already underway — climate change — and will encourage future waters to run off the surface into the ocean, where it will accumulate, change the temperature, the salinity, the currents and, ultimately, our climate.

The cryosphere, the frozen part of our world, and the glaciers3 that make up most of it were made into monolithic bodies long ago, the glaciers of our geographic and cul- tural imaginations. They have been depicted — either from above through satellite imagery or below, photographed or filmed as glacial tongues moving back toward the sea — as slow-moving masses of ice and snow. To be glacial has meant, until now, to be imperceptibly slow. The seemingly endless stream of numbers that are supposed to commu- nicate climate urgency to us, like degrees warmer, meters rising, species disappearing — have been (and continue to be) represented, when it comes to the melting of glaciers, by what appears to be an absence. Distances between before and after4 are brought into relation by comparing photographs of bodies of ice.

It is at the nexus of work presented by the photo- graphic series of Robert Zhao Renhui, the film-based re-search of Susan Schuppli, and the alternative cosmology of ice in the work of Nico Alexandroff where, between before and after, we find now. And it is here, as Lukáš Likavčan suggests, “within the risky and ununified nature of our perspectives can we learn to describe the real terrain of what it means to be an Earthling.”5

In 2011, Robert Zhao Renhui travelled to the Arctic Circle to photograph and document glacial and polar activities — and the humans, some scientists, artists, and activists interacting with and within them. The Glacier Study Group series acts as a double index, with Zhao’s critical lens capturing a zoological gaze, the curious, sometimes perplexing ways humans grapple with their surroundings. Functioning as a kind of scenography, they point to the objects they sought to depict — the glaciers and the humans — and to social, political, and material contexts within which they were made.

A few years later, on April 2, 2017, in Edmonton, Canada, the cooling system of a storage freezer in the Canadian Ice Core Lab (CICL) failed. Trying to correct itself, the system began to push warm, heated air into the usually-40-degree Celsius room. Within a few hours, 180 ice cores that had been gathered from across the Canadian Arctic over the last 50 years were reduced to steaming puddles of water. Within a few hours, tens of thousands of years of Earth’s climate history vanished.6

NICO ALEXANDROFF is a research-architect based in London (MA Architecture, Royal College of Art). His work has featured in exhibitions in Glasgow, Prague and Karlsruhe, and he has written for publications including Columbia GSAPP and the RIBA. Nico is a design tutor at the Bartlett School of Architecture and recently established AfterBodies—a design-research collective. He is currently a PhD candidate at the Royal College of Art, researching cosmologies of ice in relation to climate collapse.

ROBERT ZHAO RENHUI is a multi-disciplinary artist and the founder of the Institute of Critical Zoologists. His artistic practice addresses the human relationship with nature. Zhao received his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Photography from the Camberwell College of Arts and London College of Communication. He was awarded the Young Artist Award by the National Arts Council in 2010 and was a finalist for the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award 2017 and the 12th Benesse Art Prize in 2019.

SUSAN SCHUPPLI is a researcher and artist based in the UK whose work examines material evidence from war and conflict to environmental disasters and climate change. Her current work is focused on ice core science and the politics of cold. Her creative projects have been exhibited throughout Europe, Asia, Canada and the US, while her writings are published internationally.

ELISE MISAO HUNCHUCK is a landscape researcher, editor and educator trained in landscape architecture, philosophy and geography (University of Toronto, CA). Based in Berlin and Milan, her work uses cartographic, photographic, and text-based practices to the document political ecologies, exploring material landscapes and relationships between resources, infrastructures, natural processes, human and other-than-human existences. She is a visiting lecturer at the Royal College of Art School of Architecture, a senior researcher and lecturer at The Bartlett School of Architecture, London, and a member of the editorial board of Scapegoat. She is also the editorial curator for transmediale.

The climate models from which we derive our predictive forecasts are based largely on models built upon the observations and conclusions gathered from ice core analy- sis. But models are far from perfect: a positive feedback loop called polar amplification makes the Arctic even warmer than local net radiation balances might predict otherwise. It is in these moments, where scientific knowledge and communication falter, where dissonance and friction emerge, that we become momentarily aware that models and measurements and photographs are but a part of “a broader ecology of ways of knowing and mediating knowledge”.7

Susan Schuppli’s interest in ice cores and the archive of the CICL began when she learned of the freezer’s failure, and it is within those very freezers that we learn from ice alongside her. The resulting filmic work Learning from Ice (2019–2021) reconfigures and recasts glaciers as a “vast information network composed of material as well as cultural sensors that are registering and transmitting the signals of pollution and climate change.” Schuppli, alongside her collaborators, is only able to successfully do so by purposefully and carefully bringing together “different knowledge practices from cryospheric science to indigenous traditions that engage with the material conditions of ice.” 8

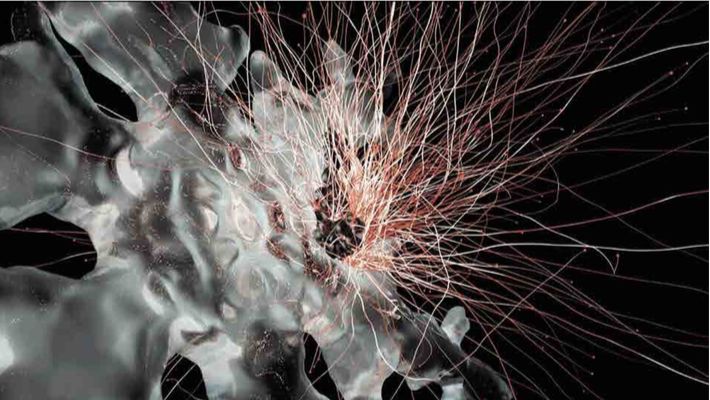

While Schuppli’s work develops forms of public narration to communicate scientific and other knowledge-making processes, Nico Alexandroff uses three recently discovered environmental phenomena — blooms, plumes, and flour — to create moments of visual and cognitive dissonance. These moments give the viewer pause so that they might become aware of their assumptions about how scientific visualizations, climate modelling and photographs themselves present so-called facts. And while Zhao’s photographed images act as a double index, Alexandroff’s work understands the ice itself as an index, acting as a boundary for consideration. Using the diagram to create an alternative image of ice through the material, political, financial, social and ecological perspectives that meet through blooms, plumes, and flour, Alexandroff also develops a form of collage, bringing together the scientific aesthetics of the report, the planetary gaze of the satellite and the molecular focus of the microscope. By bridging the planetary and the molecular, Alexandroff’s multiscalar images position the human within planetary processes, drawing together mediums and persons that would not normally be placed together to orient us towards a new cosmology.

Rightly or wrongly, glaciers have become proxy landscapes for communicating planetary climate change. Although it is widely accepted that glacial loss will hinder scientific research as well as affect the oceans of the world, the ineffectual communication of the urgency of their melt- ing future is striking. But it is not inevitable. The practices of Alexandroff, Zhao and Schuppli move beyond the before and after to the now. Their critical image-making not only tells us of glacier’s formations, movements, and seemingly inevitable melt, but it also provides us with needed moments and glimpses to understand glaciers as entities that, like ourselves, are entangled together in the complex, interrelated system of planetary metabolism.

Authors note: Thank you to Nico Alexandroff, Robert Zhao Renhui and Susan Schuppli for their time and generosity in sharing both their work and reflections.

1 From the Fourth Tractate of the Six Enneads by Plotinus: http://classics.mit.edu/Plotinus/enneads. mb.txt

2 The Summit Station is located at 72.58°N 38.46°W.

3 Glaciers begin to form when snow falls, remains, and accumulates in the same area throughout the year, year after year. As layers of fresh snow fall onto the older snow, particles like soil, pollen, particulate become trapped between old snow and new snow and as the weight of the new snow presses down, material traces of the time between snowfall and compression become trapped between molecules and within small air bubbles. As

the snow turns into ice, and as the ice begins to flow outward and downward under the pressure of its weight, it becomes a glacier. However, until this phase of solidity, air and air bubbles are free to move amongst the snow crystals. The air, later released through the examination of ice cores, can, counterintuitively,

be “younger than the frozen substrate that contains them” (from Susan Schuppli’s Field Notes).Thus

glaciers come together as communities of individuals, living and nonliving, under pressures of temperature, atmosphere and time. Ice cores are but samples of these communities.

4 Before and after what, we might ask.

5 Lukáš Likavčan, curatorial text, Fotograf Festival #11 Earthlings

6 Despite the mechanical failure, the CICL still holds 1317 ice core samples at a total length of a 1.4 kilometers of ice spanning just under 80,000 years. From: https://www.ualberta.ca/science/research-and- teaching/research/ice-core-archive/index.html

7 This broader ecology, referred to in the curatorial text of Lukáš Likavčan, can be seen in Susan Schuppli’s Can the Sun Lie? (2015), where we learn that observations first made by Inuit as to the changing climate — such as the setting of the sun changing positions along the horizons, later shown to be due to warming Arctic air — initially denied by the scientific community, are only retroactively accepted when Western science renders it both knowable and sensible.

8 Elise Hunchuck. Olafur Eliasson: Planetary Metabolism and the Charismatic Landscapes of the Cryosphere. Flash Art, 331 summer 2020. https://flash—art.com/article/olafur-eliasson- planetary-metabolism-and-the-charismatic-landscapes-of- the-cryosphere/#_edn7

#40 earthlings

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face