Sarah Lucas

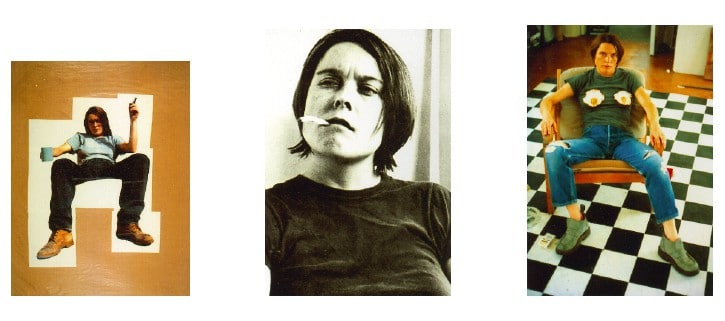

This characteristic self-depiction can easily be compared with the work of her friend, Tracey Emin, and, in 1993, the two artists collaborated on The Shop in Bethnal Green. However, their work is essentially different. While Emin’s self-confessional stories reveal her personal life, Lucas uses her image in a more general way, playing on the viewer’s automatic stereotyping response and blurring the distinction between truth and fiction.

Before arriving at Goldsmith’s College in 1984, Lucas completed a foundation course at the London College of Printing. It seems amazing now that when Lucas’ work was included in Damien Hirst’s Freeze show in 1988, she was the only artist who failed to sell anything. Having since shown solo worldwide, had work included in numerous group exhibitions, and been the subject of a BBC documentary, Two Melons and a Stinking

Fish (1996), it is not surprising that her work regularly commands large sums. The top hammer price at auction now stands at £120,000 for the series of photographs, Fighting Fire with Fire Six Pack (1997).

“Most of my best things are flippant in a way,” says Lucas, “the interesting thing about being flippant is that you can’t really contrive it – that would be a contradiction. You would need circumstances in which that kind of flippancy can occur.”

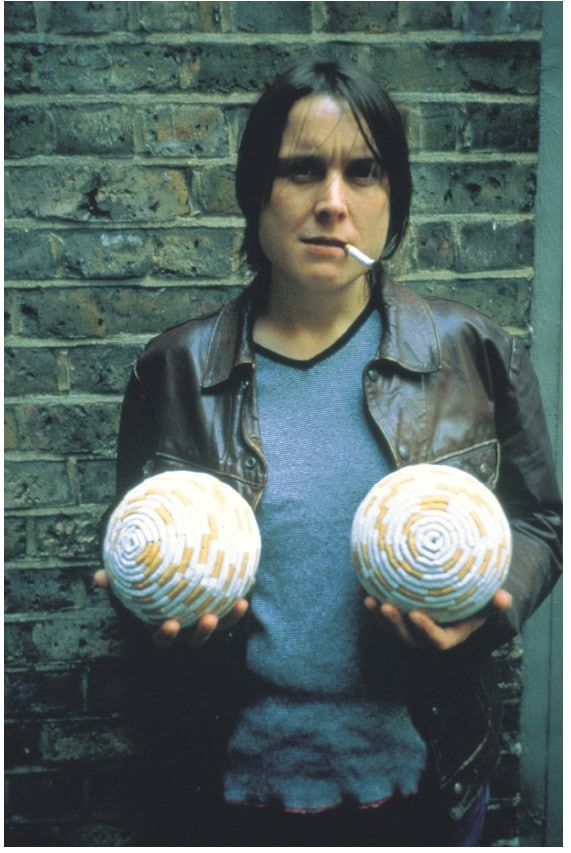

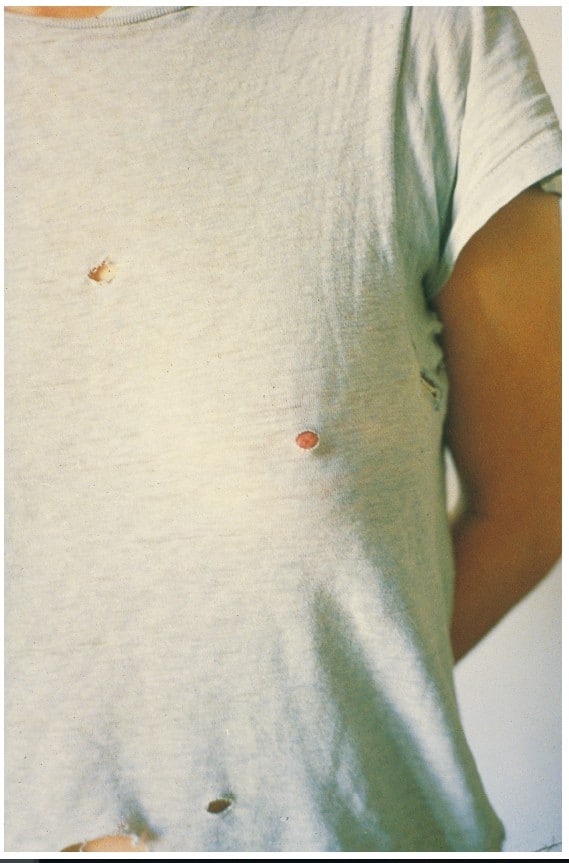

Some of Lucas’ sculptures work in the same way as the tabloid headlines she began using in the early 1990s. The viewer is, in both cases, simultaneously repulsed and fascinated. Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992) resonates with connotations of how men joke about and perceive the female body, and similar gender stereotyping is referred to in 1994’s Au Naturel (above). References to male genitalia are also made – for example the bottle of milk and pair of digestive biscuits that cover the man’s crotch in the series of photographs, Get Off Your Horse and Drink Your Milk (1994).

However, the initial simplistic visual impact only briefly masks the layers of meaning that resonate within Lucas’ work. Through the use of everyday objects that include garden gnomes, hoovers, chairs, tables, mattresses, vegetables, clothes, toilets and lots of cigarettes, Lucas conjures up a diverse range of art historical references. These can jump from Marcel Duchamp to Allen Jones or from René Magritte to Rachel Whiteread. But even the use of such references is not clear-cut – some are used with a touch of deference while others can appear to mock.

“There’s always that bit missing in Sarah’s work,” fellow artist, Damien Hirst, has commented, “There’s no way out, no way in, but you’re in. It’s like a bogey on your finger. That’s what makes her so brilliant.”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/news_comment/artistsinprofile/lucas.shtml

This text was written for a three part documentary entitled Britart, which was broadcast in June 2003 by the BBC. The series dealt with a thirteen year period in British art, dating from the revolutionary exhibition Freeze, organized by Damien Hirst in 1988, until the opening of the Tate Modern in London, the first major museum of contemporary art in Great Britain. Those years saw the crystallization of Britart, a movement characterized, among other features, by a certain tendency towards the scandalous that often reaches such a degree that it makes the artists trendsetting celebrities. Besides Sarah Lucas, other artists associated with Britart are Abigail Lane, Gillian Wearing, the Wilson twins, Sam Taylor-Wood, Damien Hirst, and others. Sarah Lucas was born in 1962 in London, where she lives and works until today. She works in various media, creating photographs, sculptures and installations. She often utilizes images of herself, and by stylizing herself in masculine poses she attempts to upset gender stereotypes.

/sarah the proletarian/

Lion Heart, a story about the clever fisherwoman and an impossible task – to bring the king a gift – or non-gift, Concrete Shoes. Au naturel, the way society looks at women and depicts women, Sarah Lucas and her self-portraits: In the center of her interest is the catching of stray remarks, arrogant innuendos, traces of the degrading of women to the role of an object. She focuses on both verbal and non-verbal comments from everyday situations. The attitude demonstrated in her photographs is the result of a long term observation. Photography as a visual rendition of the self-portrait, her daring presentation enriches society not only by providing a new discourse – the position of a woman artist in society today – but also in terms of art theory. At the beginning of the 1990s, Sarah found a new way of decoding the symbol.

Her conception of the self-portrait does not have a pragmatically defined attitude or a pedagogical grasp of the theme, and nor does it have an ideological underpinning. By positioning herself as both object and subject in her photographs, emphasising the weight of her body, she includes in her concept the demeaning, humiliating force of prejudice, the ambiguity of some sayings, words, and symbols. Her realizations give the viewer – depending on his or her sex – an intense emotional experience. Either as male fantasy, or as female fear. Sarah keeps aiming at a certain hybrid quality – a loose whole in which individual parts are recognizable. The figures Sarah creates in her self-portraits are a deliberate combination of various and often contradictory encoded symbols and an almost minimalist reduction. This reduction of means does not create a monument to resistance or provocation, but rather a space through which the viewer can penetrate down to the psychological levels of the origins of each self-portrait.

“A couple of things have come about in a fit of anger. I think it’s more a reflection on myself, or on things in general rather than anything specific. Maybe it’s just trying not to feel powerless, and one thing about feeling powerless is that what you are up against is so faceless, it’s like banging

your head against an invisible wall.”

#3 Transforming of Symbols

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face