From the Rhetoric of the Image to Notes on the Index

May it be argued that a parallel history of photography began being written in connection with the formation of conceptual art? At a time when the institutionalization of photography, qua a specific artistic medium (the allocation of photography collections, galleries, university curricula), was occurring by degrees, conceptual art revealed the possibility of viewing photography in a new way by beginning to consistently render uncertain and exceed the medium’s traditional boundaries. As a result, this type of photography entered the history of art a bit through the back door – decidedly not thanks to loudly exacting attention; potentially based on proving its own “artistry.”

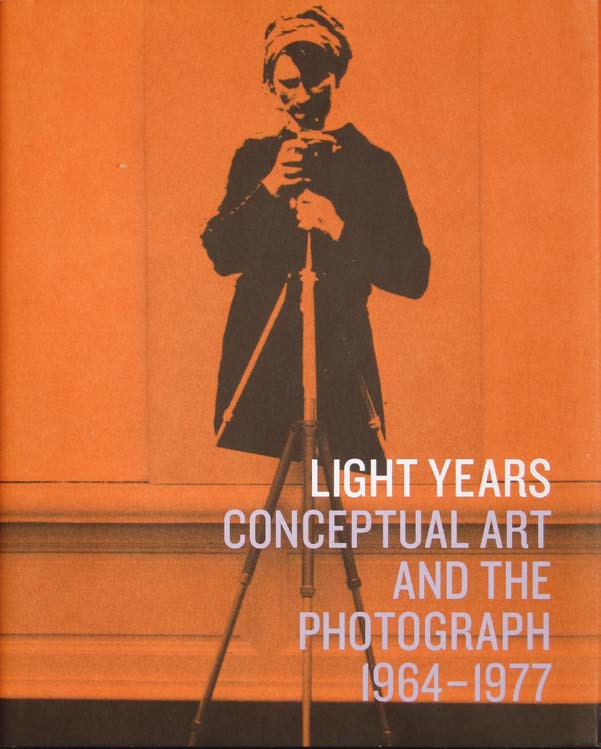

A contribution to the present-day discussion about the relationship between conceptual art and photography was recently made by the exhibition Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph, 1964–1977 (December 13, 2011 – March 11, 2012), which Matthew S. Witkovsky prepared for the Art Institute of Chicago. The name of the exhibition’s curator is not unknown in the Czech Republic, for Witkovsky belongs to those few foreign researchers who have also been dedicating their attention (and not only that) to Czech art; (he has written, for instance, about Jaromír Funke and Milča Mayerová, and, in 2007, for the National Gallery in Washington he put together the extensive exhibition about modern photography in Central Europe, Foto: Modernity in Central Europe, 1918–1945).

In the introductory essay of the Light Years exhibition catalogue, Witkovsky partially reveals the “prehistory” of a conceptual use of photography. In this context, he first mentions dada, surrealism, constructivism and the 1930s in general. He also draws attention to the fact that during this same period of time, as part of the effort to describe the history of photography up to that point as an art history, the term “medium” started being used so that the uniqueness of photographic representation could be proven through “media specificity.” The 1950s were primarily fundamental for a subsequent development by means of a mass diffusion of photographs. Then in the following decade, the hitherto existing understanding of a photograph as a two-dimensional image on a piece of paper significantly changed thanks to conceptual artists. Rather than working with traditional photography, they began to work with all of photography’s possible forms. They exhibited original books and magazines; transferred photographs onto canvases; projected diapositives… Of course, an enumeration of ground-breaking works is not complete without Twenty Six Gasoline Stations by Ed Ruscha (1963). In 1966, key works in just then emerging photo-conceptualism came from Guilio Paolini, Dan Graham, Mel Bochner and Bruce Nauman. Supposedly, the lastly mentioned author began dedicating himself to photography after having seen Man Ray’s retrospective in Los Angeles in 1966 – his famous photograph Self Portrait as a Fountain also comes from that time. In 1969, Vito Acconci’s Twelve Pictures substantially contributed to a further confusion of boundaries, that is to say of those between performance and photography. And so, in this manner we could go on with Witkovsky.

We should also mention, at least briefly, the other authors (and their contributions) invited to collaborate on the publication: curator of the Tate Modern in London, Mark Godfrey; professor of photography at Harvard University, Robin Kelsey; Chicago art historian Anne Rorimer; Italian art historian Giuliano Sergio; and University of Maryland professor of art history, Joshua Shannon. In his text, Mark Godfrey unravels the relationship between conceptual art, travel and photography, and thus traces the new distributional channels that started being used in the ‘60s by artists like Stephen Shore, On Kawara, Eleanor Antin and Douglas Huebler. The intentionally uninteresting photographs of Douglas Huebler, as well as other “chance” images created based on a predetermined plan, are also the material Joshua Shannon deals with. In the middle of the ‘60s, John Baldessari started exploring the possibilities of applying chance to photographic representation. The results of this process and of the relationship between performance and photography is treated by Robin Kelsey’s study. Giuliano Sergio’s text elucidates in what way the artists of the Italian arte povera movement made use of photography. The theoretician of this group, the Genoese critic Germano Celant, understood at that time that photography can contribute to a redefinition of the relationship between an artist and the public. Sergio likewise exalts Piero Manzoni, who was one of the first Italian artists to contribute to an innovative method of working with photographic documentation. Anne Rorimer’s text closes the book by pointing out, amongst other things, the various ways photography entered into a dialogue with traditional art forms.

The delimitation of the examined time period as being from 1964 to 1977 is obviously not a random one. Witkovsky anchored the output of his research via two key theoretical texts. In 1977, Rosalinda Krauss published her two articles about the relationship between indexicality and fine art in October magazine. The articles present an important shift in the field of theory of the ‘70s (Notes on the Index was published in Czech under the title Obraz, text a index: poznámky k umění 70. let). In them, the author returns to the equally as famous today text, Rhetoric of the Image by the French philosopher Roland Barthes – especially to his semiotic reading of photography – and adopts Barthes’ term, “message without a code.” The theme of the entire book spins in a circle connecting Rhetoric of the Image and the moment when it is cited by Rosalinda Krauss, even though it must be said that this movement is far from any closure. In the introductory essay, Witkovsky indicates that the source of a conceptual use of photography can already be observed in the first half of the 20th century. Even so, it is apparent that something crucial happened in the second half of the ‘60s, which was then further developed by the works of the nowadays well-known “artists working with photography”: Jeff Wall, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman – and it is alive in art to this day. As shown by Light Years, it is “something” much less dematerialized than what we could have expected from conceptual art.

Hana Buddeus

Matthew S. Witkovsky (Ed.), Light Years. Conceptual Art and the Photograph 1964-1977, Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago / New Haven: Yale University Press 2011

#19 Film

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face