Martina Mullaney

Usually She Is Disappointed

We suffered terribly as we became our separate selves.

Virginia Woolf, The Waves, 1931

Anna, Anna, I am Anna, she kept repeating; and anyway I can’t be ill or

give way, because of Janet; I could vanish from the world tomorrow, and

it wouldn’t matter to anyone except to Janet. What then am I, Anna? –

something that is necessary to Janet. But that is terrible, she thought, her

fear becoming worse. That’s bad for Janet. So try again: Who am I, Anna?

Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook, 1962

To come into being, the Greek philosopher Empedokles argued, is to be

a part of a mixture. To separate is to cease. Empedokles proposed that

everything except fire, air, earth, and water is perishable. All four of these

elements exist eternally, and are held together (suspended) in a solution

which he called Love. The world as we know it can therefore only exist, he

argued, when both Love and Strife are present: birth being the mixture and

death being the separation of what had been mixed. In our current sociopolitical

and socio-ecological climate, existence seems to have become

increasingly preoccupied with strife, exposing us to an intensified sense of

separation and loneliness, in spite of our shared vulnerability.

Usually she is disappointed (2018) by Martina Mullaney questions

whether art can find a way of overcoming this atomizing isolation and

resulting loss of sensitivity. Evolving over a period of two years, this

collection of images attempts to make sense of the interconnected

relationship between artist, mother and institution; between public, politics

and compassion.

These concerns emerged from Enemies of Good Art, a project

initiated by Martina Mullaney in 2009, which took its title from the infamous

quote by author Cyril Connolly, who, in his 1938 novel Enemies of

Promise, asserted that “there is no more sombre an enemy of good art than

the pram in the hall.”

Enemies of Good Art debated the issues arising from this infamous

quote, through public meetings, seminars and workshops, in order to

temper the separation experienced by artists with children in the art

world, and by proxy, within capitalist systems. This was achieved through

developing public discussions and art-based child-friendly events.

Driven by the realization that Western, post-industrial social structures

are not going to end well, Mullaney’s creative practice has become

increasingly concerned with finding visual and performative methodologies

that might invoke a sense of solidarity between different publics, but

particularly between the institution and the maternal. The causes of

separation, her work suggests, are not just confined to war or totalitarian

ideologies; they also reveal themselves daily in the failure to react to

someone else’s suffering, in refusing to understand the needs of others, in

insensitivity, and in eyes turned away from a silent ethical gaze.

The number of images that make up Usually she is disappointed

reflect Mullaney’s resolve to ensure that we cannot turn away, that we

cannot be quietly ushered, screaming child in arms, towards the exit. She

argues that we are all implicated and that, most importantly, we are living

through a time and place loaded with implicit cultural boundaries; where

restrictive social pressures continue to prevail and where the expectation to

conform comes as much from within as from outside.

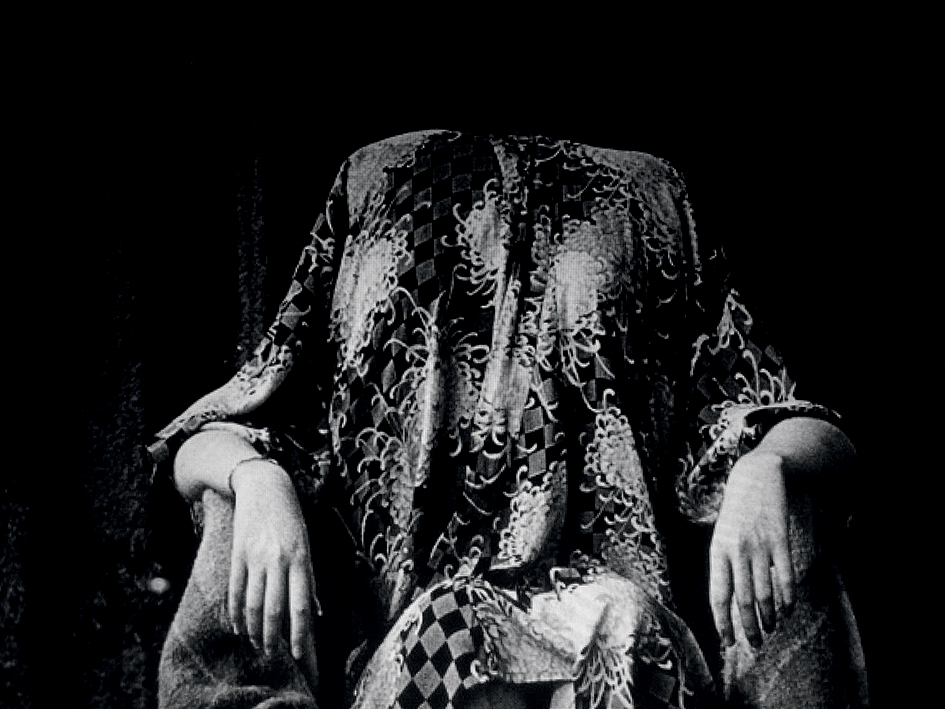

Mullaney’s black and white compositions contain close-up

portraits from found images, including of French psychoanalyst Luce

Irigary and feminist philosopher Helene Cixous as well as the British

sculptor Phyllida Barlow and New York painter Carmen Herrera. These

women were the catalytic agents for Usually she is disappointed and

provide a context for Mullaney’s thesis because they all share, to some

extent, the belief that a breakdown (of the mind, of the body, of the art

world, of an artwork, of society) is also a breakthrough. It can lead to a higher sense of understanding, releasing the architecture of the spirit

from material and maternal confinement. This theme of breakdown is,

according to author Doris Lessing, a way of addressing and dismissing

false dichotomies and divisions1.

Lessing believed that Art during the Middle Ages was communal

and un-individual. It came out of a group consciousness and did not have

what she described as the “driving painful individuality of the bourgeois

era”.2 Like Lessing, Mullaney’s work is concerned with moving beyond the

egotism of individualism, turning instead to a form of art-making concerned

with expressing the need to take responsibility for each other rather than for

our individual and separate selves.

This notion is exemplified in Mullaney’s decision to include an image

of Savita Halappanavar, a 31-year-old Indian dentist who died in Ireland in

2012 from a septic miscarriage, in the collection of images that make up

Usually she is disappointed. Halappanavar’s miscarriage took seven days

to unfold, and in that time she had asked repeatedly to have a termination,

knowing that, with ruptured membranes, her risk of contracting an

infection would be very high. The medical team did not judge her life to

be in danger, which was the only means by which a woman could have an

abortion legally in Ireland. Up until 2018 the act of abortion, where there

was no immediate physiological threat to the woman’s life to continue

the pregnancy, was a criminal offence punishable by life imprisonment.

Halappanavar’s unnecessary death caused substantial controversy in

Ireland leading to protests and marches. Later, she became one of the

many women to be remembered by those who campaigned to repeal the

Eighth Amendment3, allowing abortion to take place.

Halappanavar’s warm smile is adjacent to Kate Middleton, the Duchess

of Cambridge; waving demurely in Usually she is disappointed. We are

invited to consider the relationship between these two figures. A relationship

that Mullaney further complicates when she includes a laughing/screaming

found image of the American painter Alice Neel along with an image of the

artist Paula Rego, who famously locked her children out of her studio, as well

as a portrait of a child by Dorothea Lange, living in the dust bowl of America

during the Depression of the 1930s.

Other images Mullaney selects from visual art and culture include

a found image of the artist Catherine Opie, breast feeding her child, the

cultural theorist Stuart Hall holding one of his children, and Leonard Cohen

with an arm around a dog. Amidst these found images, Mullaney captures

fragments from her own experiences. Glimpses of the artist’s daughter are

visible alongside a line of washing, a pet dog, kittens, a flock of seagulls, toys,

a monkey carrying her baby in a tree, morning light in a small sitting room.

Through these diverse groupings of images, Mullaney explores the

idea of the maternal, the experience of motherhood and the histories of

feminism in all their complexity.

Mullaney amplifies the importance of these interconnected

relationships through the use of text. Written in white on a black

background beside each image is the word ‘seminal’. The etymology

of seminal, notes Mullaney, comes from the term ‘of seed’ or semen.

Figuratively, the term in the 17th century was used to mean ‘full of

possibilities.’ Mullaney notes that there is no feminine equivalent to the

word seminal. Her decision, therefore, to place this term beside images

that reflect the poetry of the everyday, the experience of separation, the

economic and practical demands of childcare, familial relationships,

celebrity, domesticity and loneliness, are part of Mullaney’s on-going search

to make a more thorough and less binary representation of what it means to

be an artist parent, or, more specifically, what it means to be a mother.

The images comment on the exclusion of women from the Academy,

their prosaic nature a reaction to the biologically driven representations of

motherhood seen within the Academy. What defines one person as a mother

doesn’t necessarily define another as a mother, and, more often than not, representations of motherhood within the Academy (if they are present at all)

prevent viewers from seeing the multiple subjectivities of the maternal.

Applying the term ‘seminal’ to the seemingly arbitrary collection of

images that Mullaney has collated to make Usually she is disappointed,

comments on the patriarchal nature of language and reveals what it means

to experience the hypocrisies and dualities, hierarchies and insecurities of

a neoliberal and capitalist art world, a world which often hides behind what

Mullaney describes in her writing as a bohemian veneer, where solidarity is

implied, but not necessarily offered and rarely experienced.

Daily life as an artist and mother living through this period in history

is honoured in Mullaney’s work in two ways. Firstly, through her decision

to define each of her selected images as ‘seminal’ and secondly by

disseminating those seminal images across social media platforms.

Exhibiting new work daily on social media allows Mullaney to remain

connected to her fragmented artistic community, a community which was

established in London and beyond before motherhood. In so doing, she

reaches out to those artists and parents who no longer live in the major

cities where they once studied and led promising careers. This is because

more often than not these cities can no longer offer them the support they

need to survive as artist parents.

Using social media as a tool to circulate her work also helped Mullaney

to initiate further discussions on what it means to inhabit the world as an artist

and a mother, two worlds so often characterized by very separate duties and

roles. By opening up this discussion, she continues the conversations she

originally started with Enemies of Good Art, and, through these conversations she, along with those with whom she engages, experiences a momentary

catharsis from the singular archaisms they are required to adhere to.

By giving credence to the lived experience of the artist mother, Mullaney

shows us a space of becoming rather than a space imbued with discrete

and exclusive categories of being. This space of becoming sits between

experience and expression, existence and essence: the fertile, complex and

anarchic spaces of Love and Strife in which we actually live. Hers are the

locations where acts of love are as much acts of defiance, where we are

“both more and less than the categories that name and divide us”.4 It is in this

space of awareness and becoming that, as Woolf points out, “our life adjusts

itself to the majestic march of the day across the sky.”5 For Mullaney, the sky

may be darkening, but the door still opens, the door goes on opening.

Ciara Healy-Musson

1 LESSING, Doris (1962) The Golden Notebook. New York: Simon & Schuster.

2 Ibid

3 Written into the Irish Constitution in 1983, The Eight Amendment recognized the equal right to life of the mother and the unborn. Making abortion a criminal offense.

4 FINN, Geraldine. (1992) The politics of spirituality: the spirituality of politics. In: Berry,P. and Wernick, A., eds., Shadow of Spirit: Postmodernism and Religion. London and New York: Routledge.

5 WOOLF, Virginia. (1931) The Waves. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

#32 non-work

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face