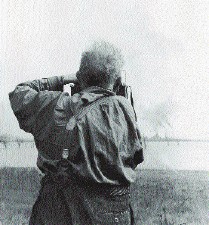

Sudek’s most region, according to Antonín Dufek

The second posthumous edition of Sad Landscape (Northwest Bohemia) 1957-1962 by Josef Sudek (1896-1976) is of uncommon significance. It consists of reproductions of 89 panoramic photographs from the collec- tion of the Moravian Gallery in Brno. Its head curator, Antonín Dufek, in his epilogue to the edition (published also in English and German) interprets Sudek’s Most region as an image of ”destruction, death“. This brings us to a matter sensitive beyond others – that of interpretation.

The fact that the original intention to title the book Severní krajina (Northern Landscape) has not been respected is justified here by Antonín Dufek by a quotation from the photographer regarding the melancholy of the landscape in the foothills of the Krušné hory region (the Erzgebirge), and in the images themselves he finds an equivalent in the depressing greyness of the sky. He then writes: “The Most region work also occupies a specific place within Sudek’s art, in terms of ‘craft’, as if the artist were trying to challenge with his positives the vaunted precision of the platinum print. The fact that Sudek’s photographs were difficult to reproduce, as well as their lack of immediate appeal, were certainly among the reasons that the book was not published.“At the time when Sudek intended to publish Severní krajina as a book, he made repeated use of gravure printing. He used this technique in his published albums, such as Praha panoramatická (Panoramic Prague), (1959), Karlův most ve fotografii (Charles Bridge in Photographs) (1961) and Janáček – Hukvaldy (1971). Negatives served as a matrix for etching the copper cylinders. It is absurd to assume that somebody would ”re- photograph“ the dark positives from the models of Severní krajina from the time of their creation in order to get a mould for prints, when the polygraphy of Panoramic Prague was based on the original Sudek negatives. The positives were thus used exclusively for purposes of orientation during the printing process – from editor, to editor in chief, to a montage of the images in separate folios. In contrast to the negatives, the positives of the Prague vedutes survive in the Odeon Publishers archive. Odeon used them to produce an new offset edition of the album in 1992, which lacked the subtlety and depth of the older version. This gave rise to debates about which technology should be considered more authentic (see the issue of the monthly Fotografie from September 1992). Personally, I believe the decisive factor to be that according to eyewitnesses, Josef Sudek personally supervised the printing of Panoramic Prague. In this respect, I now view most favorably the pre-printing treatment of KANT publishers, and the finalization of Sad Landscape undertaken by the firm Pb tisk of Příbram: in terms of the quality of polygraphy, the album comes close to the older quality of detail, down to the canvas binding.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Odeon donated 284 archive contacts for Panoramic Prague to the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, and these 10 × 30 cm contacts served as the basis for many exhibitions. As a similar event, the travelling exhibition of Sad Landscape (Northwest Bohemia) 1957-1962 may be considered as an instructive undertaking, even though the photographer made prints of his panoramic items in the ratio of roughly 20 × 60 cm. This was the size, for instance, of the vedutes one had the chance to see under the title Mostecká krajina (Landscape around Most) during the recent comparative exhibition of Sudek and Filla in the Gallery of the City of Prague. These came from the collection of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, which owns 25 1960s-era prints of Sudek’s panoramas.

In this light it appears that the epilogue of the present book ignores at least one of the characteristic and essential traits of the panoramic image. In the reading of Antonín Dufek it bears ”the ethos of a truthfulness that holds nothing back, that does not select or omit; the ethos of the exact description, the exploration of the world. At the same time it is the ethos of service to reality towards which the artist bows in humility.“

In the same epilogue, Dufek quotes the photographer’s words: ”nothing can be photographed as is“, adding a symptomatic comment: ”Documentary cannot be perceived simply as a message; it is also a parable.“ Dufek’s interpretation of the contact positives of Sudek’s vedutes from the Krušné hory foothills from the Moravian Gallery collection as final works, however, provokes doubt: does not the epilogue distort the lesson learned from the exhibition?

#5 Borders of Documentary

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face