Světlu vstříc / Towards Light

Jaroslav Kučera has rediscovered several of his forgotten colleagues and presents their legacies in book and exhibition titled War Photographers / Fotografové války 1914–1918. He cites in his introduction to the book that the „images by Gustav Brož, Jan Myšička, Jenda Rajman and Karel Neubert are genuine, experienced, and they have great artistic value.“ More than two hundred historical photographs are accompanied by the facts available today, and capsule biographies of the artists. The curator reveals himself as a practitioner, distrustful of theorizing.

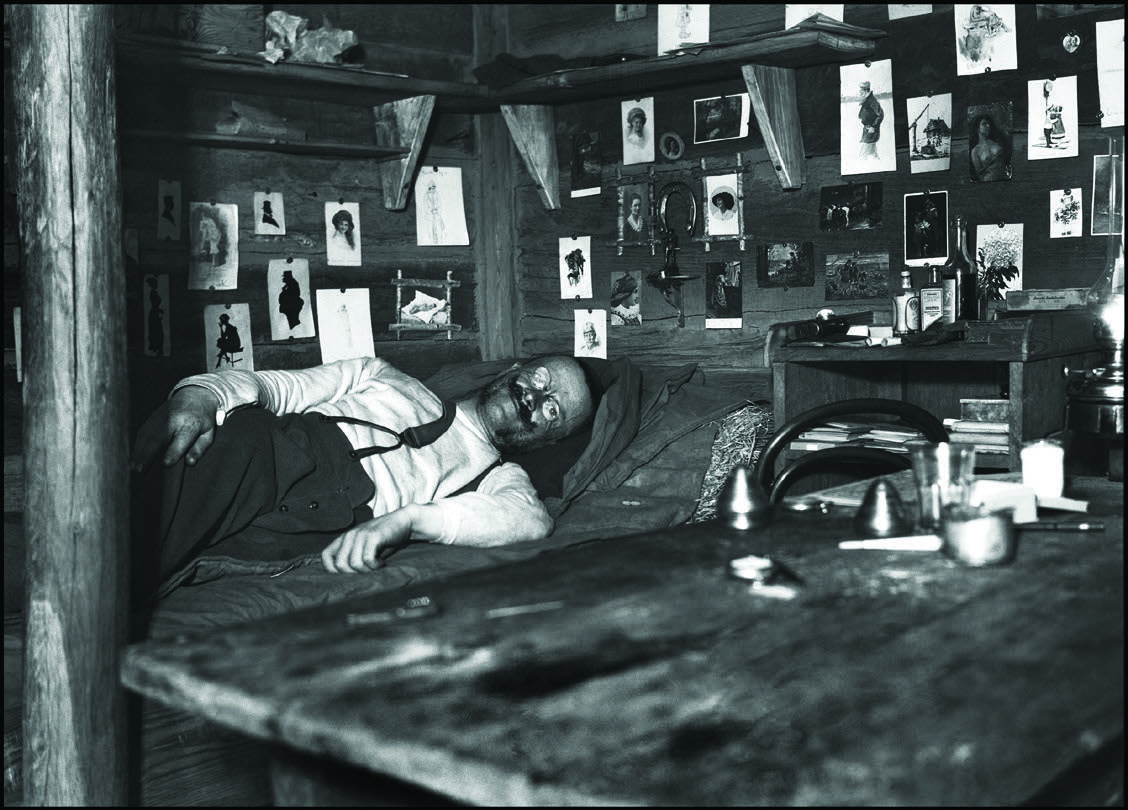

Kučera did not initially suspect how many proponents of an independent perspective he might find among the pioneers of Czech documentary war photography. He simply decided to show the brutal conflict through the eyes of those Czechs who not only participated in it, but also recorded it. “Not one of these four soldiers was a professional photographer,” he observed in a lecture given before the exhibition. “Each of them had been recruited in an altogether different capacity.”

Kučera systematically catalogued the estates of five artists; however, at the last moment, the heirs of Jindřich Bišický, the world-renowned photographer of the 47th regiment, declined to give permission to publish works to which they hold the copyright. Fortunately, if nothing else we have the monograph entitled Pěšky 1. světovou válkou (World War One on Foot), although this was published before the name of the photographer became known (as a catalogue accompanying an exhibition held two years ago, which drew twenty-seven thousand visitors).

It is likely that not all owners of photographic estates dating to the First World War responded to Kučera’s call (of international significance in this respect would also be the cataloguing of the legacy of Josef Sudek, which surely the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague will undertake at some point). Even so, as a private researcher he has made an astounding contribution to world history. Having removed the dust so to speak from the visual protocols of politics carried out within the infrastructure of the Austro-Hungarian army, he opened a way into a lost chapter in humanist photography. From a broader collection of about 3000 images taken by 12 authors, he selected the four distinguished figures, of all whom systematically documented their experiences and their surroundings. These were in general men with a keen eye, alive to the implications of what they were doing. This is attested to also by their respective body of writing. More than anything, however, it is their photographs that continue to speak for them. These provide testimony not only of the catastrophe of war, but also the sense of terror it inspired.

Numerous self-portraits indicate the confidence of the photographers, who did not know one another yet shared a common awareness of photography. With their large-format cameras, they were adept at the composition of impromptu shots, as well as also being possessed of an acute sense for lighting a scene. Where there was no other option, one can see the glow of burning magnesium, or the subtle stage-direction of the scene. Although nominally they were amateur photographers, under the impression of the situation they conducted a lonely polemic with the illusions that dictated the tone of period taste in terms of the galleries and parlours of the time. Ultimately it seems that they asserted their own vision, and thus in fact emerged victorious (a similarly spontaneous phenomenon of the First World War was Hungarian André Kertész). The images for the most part do not originate from the battlefield, whether the southern or the eastern front. This is hardly surprising: in the heat of the battle, all one could do was obey orders and try to survive. And yet the images as a whole are an indictment of the slaughterhouse mechanism of the war machine.

The exhibition War Photographers / Fotografové války 1914–1918 is presented by the Prague Castle Administration, running until September 4th 2011. The installation includes positive contact prints of the period, as well as historic cameras and accessories for developing film or plates under field conditions.

Jaroslav Kučera (ed.): Fotografové války / War Photographers / 1914-1918. Jakura & Správa Pražského hradu, Praha 2011, 184 pages.

#17 Amateur Photography

Archive

- #45 hypertension

- #44 empathy

- #43 collecting

- #42 food

- #41 postdigital photography

- #40 earthlings

- #39 delight, pain

- #38 death, when you think about it

- #37 uneven ground

- #36 new utopias

- #35 living with humans

- #34 archaeology of euphoria

- #33 investigation

- #32 Non-work

- #31 Body

- #30 Eye In The Sky

- #29 Contemplation

- #28 Cultura / Natura

- #27 Cars

- #26 Documentary Strategies

- #25 Popular Music

- #24 Seeing Is Believing

- #23 Artificial Worlds

- #22 Image and Text

- #21 On Photography

- #20 Public Art

- #19 Film

- #18 80'

- #17 Amateur Photography

- #16 Photography and Painting

- #15 Prague

- #14 Commerce

- #13 Family

- #12 Reconstruction

- #11 Performance

- #10 Eroticon

- #9 Architecture

- #8 Landscape

- #7 New Staged Photography

- #6 The Recycle Image

- #5 Borders Of Documentary

- #4 Intimacy

- #3 Transforming Of Symbol

- #2 Collective Authorship

- #1 Face